“I believe the Great Creator has put oil and ores on this earth to give us a breathing spell. As we exhaust them, we must fall back on our farms, which is God’s true storehouse and can never be exhausted. For we can learn to synthesize materials for every human need from the things that grow.” ~ George Washington Carver

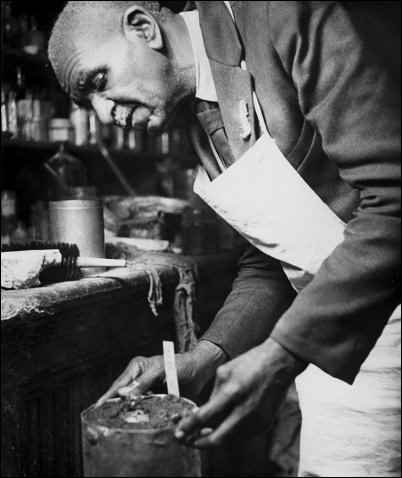

You may need to be a certain age to remember much about the Peanut Man. George Washington Carver was a scientist, an agriculturalist, an artist, a horticulturist, an inventor, an eco-visionary, a conservationist, a proponent of alternative technologies, and, for a time, a homesteader.

Because he was black, and Southern—born in a bad time to be both—his legacy is more humble than it should be, but he would not have minded. He was always that best of ideals, “the bigger man”, who lived and worked outside the world’s esteem.

Carver wrote only a little about his childhood. A modest, rather shabby, slender, dark-skinned man with a lot on his mind, he recorded that he was the child of slave parents around the close of the Civil War. He was born in Missouri; a state that did not secede and was not at war with the Union, therefore it’s ironic that it retained slavery until 1865, the probable year of Carver’s birth. The boy’s father died before he was born and his teen mother and he were kidnapped by a roving band of marauders taking advantage of the war to loot and plunder. As fate had it, George alone was rescued by his owner, Moses Carver, and spent his childhood in the rather safe environs of a large farm, the ward of white parents.

He was, as he later wrote, “feble” and had bouts of illness that nearly claimed his life more than once. For this reason, he was assigned simple tasks that included helping Susan Carver in her garden. He took to wandering in the woods and became an amateur horticulturalist at an early age. He loved flowers and taught himself to propagate plant varieties. Because of his zeal to read, he was sent to a black school in Neosho, and taken in by an African-American couple there. His foster mother was an herbalist who doubtless increased Carver’s knowledge of plant lore.

He moved on from Neosho to join the Exoduster movement (see my Homestead.org article, Exodusters: The Roots of African American Homesteading). Barely in his teens, with a thirst for knowledge he could not garner at any local school, Carver wanted to be part of this exciting trend: blacks from the Deep South occupying the new territory of Kansas, where, at one time, there was a possibility of an all-black state. This surge was the result of the Homestead Act being signed into law by Abraham Lincoln, allowing ordinary folks to gain land ownership by populating open territories and improving their smallholdings within a set time-frame.

Through the Homestead Act, the young Carver got a quarter-section of land near Beeler, Kansas, built a sod shanty, and plowed his own acreage. A Kansas Historical Marker near Beeler notes the quarter section, “Homesteaded by George Washington Carver, an African American and one of America’s great scientists.”

During his late teens and early twenties, the once “feble” Carver was pushing his physical powers to their limits, working his land and later wandering about in the Midwest, taking any odd jobs available. Carver did not consider labor to be demeaning. He was willing to do anything necessary to improve himself. At the same time, he continued to pursue education, generally disappointed by what was available. He was generally smarter than most people who tried to teach him, and when that was not a barrier, his color was.

One college, after inviting him to attend based on his application, turned him away at the door when they saw he was not white. Encouraged by white friends to enroll at Simpson College near Winterset, Iowa, Carver finally found a place where “People…made me believe I was a human being.” He studied, not science, but art and piano.

A favorite art teacher with the lovely name of Etta Budd was so impressed with his accurate and beautiful paintings of flowers that she pushed him to major in botany at Iowa State Agricultural College, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in Agricultural Science.

At this point, Carver stepped into a greater destiny, as he decided to align his forces with those of, famous fellow African-American leader, Booker T. Washington, and joined the faculty of Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Carver would say of this decision, “It has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of ‘my people’ possible and to this end I have been preparing myself these many years; feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people.” Washington, like Carver, believed that given a chance, black Americans could succeed, and both had the zeal to bring that idea to fruition. Both believed in economic independence and interracial cooperation, despite the extremes of whites’ hatred of blacks that permeated the South and many other parts of America at that time.

The majority of Carver’s adult life was spent at Tuskegee. He and Washington rarely got along, however, despite their tightly linked placement in history as role models for aspiring black students. Carver felt oppressed by the college’s incessant demands on him; he wanted to help students, but classroom teaching didn’t come naturally to him, and still less, the duties of academia such as committee work and management. Carver wanted to do research because he felt that was where his true talents lay. Washington wanted spokespeople for his institution, and simultaneously, wanted everyone involved to take on multiple duties. Even so, Washington gave Carver a certain prima donna status, letting him have a spare dorm room just for his plants, and paying him more than other faculty members.

Carver was a tinkerer, as are many of the greatest inventors, while Washington was a businessman. But both were visionaries.

One vision they shared was the idea of mobile education, so together they initiated a revolutionary program called “Movable School.” Carver took it upon himself to be an agricultural-circuit rider when he first came to Tuskegee, visiting local farmers and sharing his knowledge with them firsthand. That was his finest teaching method, and one for which he was most remembered by many young men (he called them his “boys”) who attended the Institute; standing at the front of a classroom was boring to Carver—holding a hoe was illuminating.

For the Movable School, the inventive skills of Carver were called into play: he designed a horse-drawn wagon (later a motorized vehicle) that could be fitted out with all the implements and equipment needed to teach farming and other practical techniques to rural Alabamans, on site. The wagons were purchased and the project funded by a wealthy New York philanthropist, Morris Jesup (one of Washington’s contacts, of course, since Carver did not associate himself with business outreach). The wagon program was so successful that it was adopted by the newly formed Cooperative Extension program; a Jesup Wagon sits today in front of the US Department of Agriculture in Washington DC.

Carver’s mission was foremost to improve the lives of poor farmers, whoever they might be, but always with an eye to improving the lot of his fellow blacks, many of them, like him, born into slavery and struggling to subsist. To this end, he explored the possibility of cultivating crops other than the usual cotton, which depleted the soil severely.

Carver’s fame spread when he turned his attention to the science then called “chemurgy”: the investigation of non-food uses for plants. Chemurgy was an accepted discipline that sprang up in the 1920s, finding linkages from plant substances to any possible useful product. Chemurgy could be seen as the precursor to the ethanol programs of today, since motor fuels (one name given at the time was Agrol) were a major line of interested spurring chemurgy.

Henry Ford was a noted supporter of chemurgy, and even studied the use of soybeans for car manufacturing. His “soybean car” was purportedly made from hemp and soybeans and fueled by a form of ethanol. Chemurgy made odd bedfellows, for it seems that, through it, Ford (a known racist) and Carver found some common interest. Ford visited Carver at Tuskegee and addressed him as “My beloved friend”. Carver for his part, perhaps naively, believed that industrialists like Ford were interested in fulfilling the crying needs of the poor, rather than merely lining their personal pockets. Carver, known for his tattered and sagging garb, had no interest whatsoever in the lining of his pockets, but he did have the zeal to use native plants and simple techniques to develop saleable products to raise his people out of poverty.

Carver became known as “the first and greatest chemurgist”, a title that may have given him some merited attention in the mainstream. The chemurgist movement eventually led to the use of corn for such uses as tire manufacture during World War II, when, owing to shortages of other materials, all Americans became chemurgists, gathering milkweed floss to provide fiber for lifejackets, and grow the questionable hemp plant for ropes.

But for Carver, it was all about human progress on the small scale. He applied the principles of chemurgy to do his job, and his job—whether his boss at Tuskegee agreed or not—was to help the poor. In fact, George Washington Carver could well be thought of as the greatest “alchemurgist,” turning the base material of the peanut and the sweet potato into the gold not only of other food products like oil and sugar, but also into dyes, paints, and fibers.

This investigation eventually led to his nickname, The Peanut Man, as he attempted to encourage the agricultural use of such nutritional foods as peas, sweet potatoes, soybeans, and the good old Southern favorite known as the “goober pea” or peanut. He tirelessly experimented with these food crops, proving that good husbandry—especially crop rotation—could dramatically increase yields. On a half-acre, he turned a 40-bushel yield of sweet potatoes into an astonishing 266-bushels just by practicing good conservation and what today would probably be called “intensive” farming methods. He demonstrated that depleted soil, worn out from years of mono-cropping cotton, could be revitalized by planting highly nitrogenous crops like soybeans or peas; a year of peas, a year of cotton.

But to encourage farmers to switch to these crops, to try his methods, he knew he also had to find the kind of viable markets for the off-year crops that existed for cotton.

Carver favored the peanut because it was easy to grow and provided nitrogen for the soil, but also because the nut itself is a source of protein. From the peanut, he famously developed oils, butters, milk, even medicines. Among the items listed by Tuskegee Institute as devised by Carver are lard, pepper (from the vines), candies, margarine, vinegar, and mock meats. He used peanut products for various kinds of animal feed. He developed peanut-based laundry soap, laxatives, and a quinine substitute. Convinced that peanut oil had great healing properties, he encouraged its use in massage for polio victims and administered such massage himself, free of charge. He invented peanut lotion, face bleach, hair oil, shampoo, and shaving cream. He found uses for peanuts as dyes for cloth, leather, and wood; used them for fuel bricks, glue, insecticides, and axle grease.

To read the list, one might imagine that, for Carver, the peanut could have potentially provided a living environment, a food source, and the majority of household products needed to make life more enjoyable, hygienic, and healthful. Though soft-spoken and, as noted, not a professorial type, this small, modestly clad man bedazzled academics and politicians alike when they questioned him about his ideas and his scientific output.

Sadly, Carver kept no notebooks and applied for only three ultimately unsuccessful patents. His rather small estate was willed to the museum established in his name. He was buried next to Booker T. Washington. His recipes survive, as do some of his forty-four bulletins for farmers.

In a sense, Carver’s life is both an example and a mystery. Expected to die before he reached adulthood, he became a man of faith. Carver exchanged correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi, offering nutritional advice to the revolutionary spiritual leader and his followers.

He wrote these rules for his Tuskegee students:

- Be clean both inside and out.

- Neither look up to the rich nor down on the poor.

- Lose, if need be, without squealing.

- Win without bragging.

- Always be considerate of women, children, and older people.

- Be too brave to lie.

- Be too generous to cheat.

- Take your share of the world and let others take theirs.

Probably poorly trained and educated, Carver tirelessly sought to endow others with a personal sense of wonder and a work ethic to turn that wonder to practical purposes. In 1941, two years before his death, Time magazine dubbed him the “Black Leonardo.” There is no doubt that had Carver been white, given his prodigious intellect and artistic talents, his life would have taken a very different course. But his strength lay in his refusal to be humiliated, enraged or discouraged by his circumstances.

Owing to a fire, one of Carver’s most outstanding legacies was lost: his paintings of plants. Only three survived. Like Leonardo, he was, perhaps first and last, a sensitive artist. Carver’s love for flowers never left him. It was said he literally talked to flowers and plants, a technique that has been espoused by many as efficacious in the modern era. He stated that through flowers, he talked “to the Infinite.” He always wore a flower in his buttonhole.

Since it is a cold season, and everyone needs a new recipe for a healthy, warming soup, I can offer no more fitting tribute to George Washington Carver than one of the many intriguing recipes from The Peanut Man. Think of him as you slurp:

George Washington Carver’s Peanut Soup Number Four

Boil 10 minutes in a half a cup of water: half a cup of chopped celery, a tablespoon of chopped onion, the same amount of red and green peppers mixed; add a cup of peanut butter and 3 cups of rich milk to which has been added 1 tablespoon of flour; add 1 teaspoon of sugar; boil two minutes and serve.