History’s ironies never cease to amaze me. The same day that Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, on January 1, 1863, the Homestead Act went into effect; but there was no immediate connection between these two famous pieces of paper. One was law. The other was a use of the President’s war powers to foment rebellion, to give harm and discomfort to the enemy; it could be seen, in today’s terms, as the hostile intent of a terrorist state. Only time has told us that, in the long run, the two instruments did eventually connect, and the beneficiaries of that connection were America’s newly freed slaves.

The Emancipation Proclamation only freed the slaves in the ten Confederate states, serving the purpose of inciting those suffering souls to defect from their masters and their lives of hopeless bondage to flee to the welcoming arms of the Union armies, many there to assist in quelling for good and for all the upstart South, and reuniting the broken nation.

However… despite the obvious yen of many ex-slaves to quit the South, they were not going to be allowed to claim land out West; the first requirement of the Homestead Act of 1863 for those who wanted to “prove a claim” was… citizenship. This was followed by the requirements that the claimant:

- Be 18 years old or older;

- Never have waged war against the United States (a clause both sensible on its face and also obviously intended to keep nearly all Southerners out of the game);

- Pay $18 in fees;

- Promise to improve the land with buildings, wells, and crops over a five year period.

That being accomplished and duly witnessed, the settler would own the property outright.

Ex-slaves were not made citizens until the Civil Rights Act of 1866 which declared:

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude…..”

Then, and only then, could people of color assume the right to grab the land being snatched up by Whites, proffered by their rich Uncle Sam.

Former slaves would seem to have had plenty of incentive to leave Dixie after the Civil War was finally over, and, with it, the institution of slavery. If they didn’t, it was probably because of the false hopes of Reconstruction, an idea that died on the vine in a few short years. It might have been because they were unaware of other options such as the Homestead Act, or fearful yet of what would happen to them if they removed themselves from known environs, since in former times, the punishment for such adventuring could get a Black person whipped, sold, or dead.

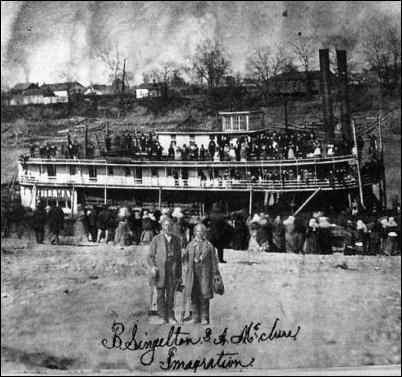

Nonetheless, there was a trickle of African-Americans westward; the migration, though short-lived, was remarkable for the numbers. The trek was labeled the “Great Exodus” and the wanderers were quickly dubbed Exodusters, an apt Biblical reference that would have resonated well with most Blacks at the time.

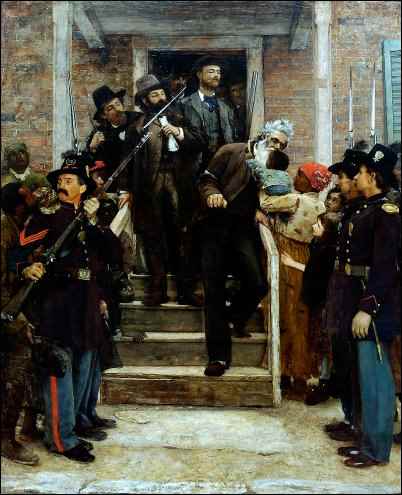

Inspired by racial separatists like Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, himself a former slave, African-Americans were encouraged to settle in Kansas, partly because of its rumored connection to the near-mythological figure of abolitionist John Brown, and in Oklahoma, which at one time was envisioned as an all-Black state. Pap, something of a self-promoter as well as a rabble-rouser, first exhorted ex-slaves to settle in Tennessee, but when locals refused to sell them land, they pushed on to Kansas, with Pap considering himself the Noah of this large migration. African-American enclaves in cities like Topeka offered safety in numbers, and Black men were quickly swallowed up into low-paid industrial jobs, their wives to domestic service. The Exoduster movement faded as quickly as it began, lasting only from 1879 to 1880, leaving its charming moniker blowing in the wind. Bad crops and fear of yellow fever along the Missouri River were two discouraging factors, especially as some locals blamed the outbreak of fever on the poor Black transients.

The Homestead Act allowed about one hundred thousand former slaves to seek claims west of the Mississippi. Despite the racial phobias that seemed to exist at all times, there was a more tolerant attitude towards every kind of strange, marvelous and scurrilous character in the wide-open spaces, where a man was judged, as one observer put it, “by how he sits in the saddle.” The Border States like New Mexico even then had a long history of accommodation to people of other races, and that made transitions for migrating Blacks less painful.

Farming was something in which many Blacks had experience, often forced under slavery’s restraints to grow small garden plots for basic survival. So logically ex-slaves might refuse farm labor, having done so much, and in fact many preferred safe city life and a regular paycheck to the risk of alien landscapes and the vagaries of agriculture. But those who were motivated by the Homestead Act were cut from different cloth from the mainstream of ex-slaves.

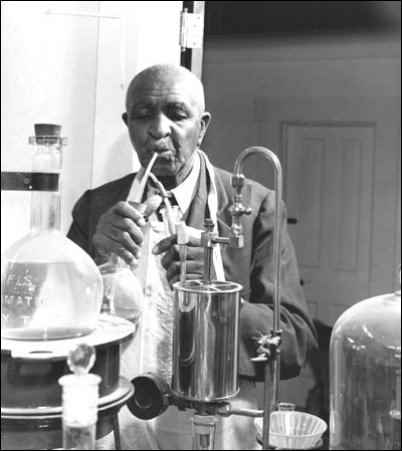

One early Black homesteader to try farming life in Kansas was George Washington Carver. The great scientist and artist settled first at Fort Scott, but left after witnessing a lynching there. Lynching was at its height in the latter part of the 19th century, more prevalent in the Deep South but not confined to that region, as Whites were unnerved by Black influx and unwilling to share living space with their African American fellow citizens. Carver homesteaded a quarter plot near the town of Beeler, Kansas, and two monuments mark his tenure there. His sod house has reverted naturally to the unrelenting flat landscape. Carver went on to teach at Tuskegee Institute, under the administration of Booker T. Washington. Both men in their own ways encouraged racial and personal self-sufficiency, and Carver’s work with peanuts and other crops to replace cotton for Black farmers was nothing short of revolutionary.

African American Henry Boyer was a wagoner for the U.S. Army in the mid-1800s. He saw New Mexico while in the service, and never forgot its beauty and grandeur or the apparently endless expanses of land available for settlement, inciting fantasies of returning someday. His son Frank grew up in the early Reconstruction years, and was educated at Morehouse and Fiske Colleges where he was inculcated with the self-help ideology of Booker Washington and the more radical philosophy of W.E.B. Dubois. When the Homestead Act of 1893 was enacted, Boyer resolved to get a parcel in New Mexico.

Appalled at the way his fellow African Americans were treated in the East, threatened by the Ku Klux Klan as a radical trouble-maker, seeing Reconstruction being rapidly deconstructed, and egged on by his father’s idealized memories of New Mexico, Frank went boldly forth: “Pursuing the dream of his father to establish a self-sustaining community, Frank Boyer and his student, Daniel Keyes, walked from Pellam, Georgia to New Mexico, stopping just long enough, to work for food, clothes, shelter, and other necessities they needed.” The trek took six months, partly because the two Black men were refused rides in passing White wagon trains. The two eventually claimed parcels of land near the current town of Roswell, later known as the center of UFO activity. Boyer and Keyes sent for their wives and in 1901, started the town of Blackdom, a play on the word “kingdom.” Boyer was a religious man and an intellectual visionary who believed that by banding together with like-minded people in a communal agrarian setting, he could attain the kind of physical, political and emotional self-sufficiency that earlier generations of his people could only dream of.

When Boyer and Keyes founded Blackdom, the region was fed with a number of artesian wells. It must have appeared like a kind of rocky paradise to land-starved Easterners. Boyer advertised for Black homesteaders who came from Kansas and Oklahoma as well as farther east. He and his wife personally helped the new arrivals build houses and plant crops. Eventually, the colony consisted of about 25 families, around 300 people, on 15,000 acres. The township had a post office, hotel, and a weekly newspaper. The center of the community was the Blackdom Baptist Church and Schoolhouse.

The community maintained an “open door” policy so that Black cowhands passing through could enter any home and help themselves to bed and board. They sometimes repaid this kindness with sides of beef. In its way, Blackdom was a utopia for its residents and a sort of “over-ground railway” of generosity and assistance for the African-Americans of the area.

Sadly, changes came about, some wrought by indomitable natural forces: “worms appeared, there was an alkali buildup in the soil, and slowly the artesian wells dried up.” It became increasingly arduous for the occupants to fulfill the requirements of the Homestead Act to “prove up” one’s right to ownership. Racial bias among certain officials continued to plague the residents as they were mysteriously forbidden from digging for water and refused bank loans. By the early 1920s, Boyer’s house had been foreclosed on, the lack of water drove all the families out to neighboring communities like Roswell, and Blackdom became a dusty ghost town. Today, it is evident only by a small monument in the trackless grasslands.

Myrtle Phillips of Albuquerque was the granddaughter of one of Blackdom’s original residents: “She and her husband still visit Blackdom nearly every year. She keeps a notebook of laminated photographs and deeds of her grandfather’s property in Blackdom. Also in the notebook are plot maps showing the location of the homestead. She has a box labeled ‘artifacts’ that is full of tin cans, pottery shards, and small pieces of adobe that she has collected from the property over the years. There is also a shiny blue piece of a plate that she finds pleasing. She has inherited her grandfather’s property and will pass it on to her children. She remembers that once her grandfather left the homestead, no one in the family mentioned Blackdom again.”

Robert Ball Anderson was born into slavery in 1843 on the Ball Plantation in Kentucky. In 1864 he escaped and joined the Union Army as part of the 125th Colored Infantry. The war ended soon after he joined up so he never saw action in that conflict, but spent the rest of his enlistment, three years, out west, finally winding up in Nebraska.

Anderson filed a claim under the Homestead Law for 80 acres of land. Like so many others, Black and White, he was unable to “prove his claim” owing to low prices for farm produce, drought, and a plague of grasshoppers, so he drifted to Kansas where he got work as a farmhand, still determined to own his own land. In 1886 he was able to secure a forest parcel, and despite many further disasters, he proved the claim at last. By considerable: Anderson and his wife became owners of over 2,000 acres in Nebraska. Their story was little different from those of many of America’s first settlers who, fleeing oppression and risking all, won the right to the soil they stood on by dint of back-breaking toil and pure grit.

Landowners like Anderson would by-pass some of the uglier manifestations of racial bias. Their lonely outposts on the prairie were a kind of protection in themselves, and Anderson was especially known and regarded as a gentleman – being a former soldier and hardworking rancher earned him the respect of neighbors who were open-minded enough to see past his hue. Anderson and others like him made it easier for those Blacks who followed later in the twentieth century.

Though the Black families who migrated West after the Civil War had more barriers to overcome than their White counterparts, all the “provers” had to fight Mother Nature in arid, lonely lands. Only about 40% of all migrants who rushed for ownership under the Homestead Act succeeded.

On the National Parks website, historian Todd Arrington observes: “Between the earlier gradual migrations and the 1879 exodus, Kansas had gained nearly 27,000 Black residents in ten years. Though a far greater number of Blacks remained in the South, this number still represents 27,000 individual dreams of a better life and 27,000 people that acted on their desires and their rights to enjoy the freedoms to which they supposedly had been entitled since the Emancipation Proclamation. Though few found Kansas to be the Promised Land for which they hoped, they did find it a place that enabled them to live freely and with much less racial interference than in the South.”