We can kick her, stick her, fog her and smog her, but she will keep on trying to give us what we need. She will always love us, whether we love her or not. Her love is demonstrable, proven in her bounty, her gentle airs and dews—a bit of fire for warmth, a taste of honey for delight. She’s our mother, whether we call her Astarte, Gaia, Pachamama, Demeter, Durga, Terra, or Devi. She answers to all, responds in kind to all who treat her with kindness, gives even to those who don’t.

So when did Mother Earth become Smother Earth, and why are people so afraid of her these days?

This is a far-reaching topic with many tendrils. One book, you would say, cannot encompass it. But one organization has made a valiant, mostly successful attempt to name names and offer evidence and remedies in the case of Human Stupidity, Greed, Violence, and Carelessness vs. Mother Earth. Hesperian Foundation, publishers of the widely read and very practical Where There Is No Doctor, have created a comparable large manual entitled A Community Guide to Environmental Health by Jeff Conant and Pam Fadem, a learning tool for development workers, for indigenous populations, and for us all. It includes case histories and accessible technologies along with horticultural, agricultural, architectural, social, and political information.

When training to work overseas, I was shown a documentary produced by the forward-thinking British aid agency, Oxfam. It described four stages of overseas development work. The first and simplest is aid in case of disasters such as the Haitian earthquake and the tsunami in Japan. Everyone can agree on the need to help in these situations; our hearts go out to the victims and many individuals chip in. Second is “teach a man to fish” or technological interventions—in this scenario the development/change agent goes into the foreign environment with a plan to promote a certain helpful industry such as well drilling or fish farming.

But, the documentary asks, what if the rich guys in the village get control of the fish farm (or the new well or the sewing cooperative)? The poorest, for whom the benefits were intended, are now squeezed out. So next comes education. People need to learn to advocate for themselves; this village-level education is often targeted to women who are powerless in most Third World cultures. But if aid, technical assistance, and education are not solving the basic problem of poverty, the last step is one that ultimately must be taken by the local people: political intervention.

These stages can be seen playing out all over the world, right now. No more so, perhaps, than in the environmental chaos that threatens so many powerless people. Gross abuses of Mother Earth abound in places where poor people, not accustomed to fighting back, have to deal with poisons in the air and the water, poisons in the food they eat, poisons in the places they work, too often the result of richer nations’ demands for goods and fuel.

This is not a new thing. Mother Earth has shrugged off a lot of human-caused abuse in her own long struggle to survive. As soon as people gathered themselves in tribes, territory began to emerge as something to be defended against others, and whole species of animals and groups of ancient people are gone forever as a result. But, for Mother, this was a small matter, as compared with what is happening now.

Overpopulation, overcrowding, industrialization—these ills began to show themselves like a slow but invasive cancer on the globe in the late 1800s. But the symptoms generally went unrecorded. We can only guess how many citizens, most of them poor, died in London and other crowded cities from inhalation of coal smoke, the infamous “pea soup fog.” This can be perhaps extrapolated from the known statistics on one unusually thick, yellow fog that enveloped London in 1952, when in all 12,000 deaths were recorded.

Deaths from underground mining were similar in nature: inhaling noxious dust and fumes, uncounted numbers of miners died from silicosis of the lungs; in fact, most miners developed some form of the disease over time. Ironically, mechanization of mining brought more problems that affected our Mother—strip mining and the most invasive, mountain top removal. In very recent times we have seen how unprepared we are for disasters—earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, explosions, erosion, floods—that devastate because of our neglect of resources, resulting in widespread after-effects that will still be felt generations from now.

But Terra soldiers on. In the mid 20th century, there were small signs of improvement among the creatures living off her abundance. People of vision began to wonder if we humans were doing right by our old Mom. The English banned coal fires from cities, and we Americans cleaned up our act with the creation of the EPA. Problem solved. Or, shall we say, problem outsourced. We are careful now how we harvest our trees, and the legacy of the Dustbowl is a more conscientious approach to large-scale farming. We eat organic when we can and decry genetically engineered food, we drink clear water, cherish clean air, and “take care of ourselves.” Yet all around the world, poor people are still burdened with our outsourced toxins. Even here, under our very noses, abuses continue, better hidden but still rife. Take for example the cultural genocide that has yet to be sufficiently redressed among our native peoples: the after-effects of uranium mining in the Southwest on the Navajo and other people in the Four Corners region. In The Community Guide to Environmental Health, there is a poignant cartoon illustration of two peasant women standing together, the younger saying of her elder, “Grandmother did not know what radiation was until it killed Grandfather.”

Like Hesperian’s other books, The Community Guide is illustrated with cartoons that would be charming were they not depicting such dire issues as dealing with mercury and pesticide poisoning, the life-threatening effects of farming and manufacturing that puts profits above people, and the harm that comes from macro-industrialization (one section is tellingly titled “Every Part of Oil Production Is Harmful”).

True stories (more than 100 of them in The Guide) demonstrate that despite their daily struggles within the first three stages of development—basic issues of food and shelter, education and infrastructure—even “ignorant peasants” have learned to act collectively to battle the invasion of exploiters. In other words, they have moved themselves to stage four: community action.

In Junín, Ecuador, for example, a Japanese company opened a large copper mine over the protests of the local people, who then organized, confiscating all the miners’ equipment, turning it over to the authorities, and burning down the camp while the miners were on vacation. The local people took these actions despite alluring promises from both companies of school, roads, and even high prices for their land.

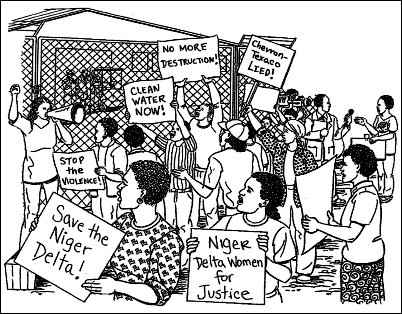

Another story highlights the rebellion of women in the Niger Delta who were oppressed by the inhumane policies of Chevron/Texaco in their region. They staged a peaceful protest by “imprisoning” oil workers and threatening to shame them by stripping naked to express their disgust for those who would work for a company that exploits their own families. In the end, these women, who were beaten and harassed by the company authorities, won major concessions including a fund to set up small businesses. Other stories of both large and small “p” political activism detail such diverse topics as a one-woman campaign in Somalia to set rocks around newly planted trees to conserve water, and the community development of biogas fuel in Nepal.

In addition to the case histories and the truly frightening warnings about industrial and environmental toxins and how to deal with them, The Community Guide also contains some useful “how-tos,” easily accessible technologies that anyone can “aprovechar” (a good Spanish word that means both enjoy and take full advantage of). These how-tos make use of affordable materials with low impact on the environment to accomplish goals of sustainability.

The A-frame level. It’s made with two sturdy sticks of equal length (about 2 meters, or 6.5 feet long), and a third stick for a crossbar. The equal length sticks need to be nailed or tied together in a triangle shape (like the hump of the A) and the third stick is attached across the other two to make the crossbar of the A. Then a string is tied to the top of the A, with a weight attached so that it hangs just an inch or so below the crossbar. The weight can be an empty bottle or a fist-sized rock.

The string and weight are now a plumb line. The plumb line was used in the building of the pyramids, and it is thought that the Arabs devised the A-frame for contouring. The terraced land of southern Spain is a spectacular example of farming made possible in steep terrain, by use of contouring with this very sort of device; that technological garden paradise was the brainchild of the Moors (Arabs) who occupied Andalusia for five hundred years, until 1492 when Isabella regained control of the region and sent Columbus sailing across the ocean blue.

With this “crude”, but functional, instrument, a farmer can plan contour lines for hilly terrain. One simply walks the A-frame around the land one plans to cultivate, and it will indicate where the level is. Even a small divergence from level can make a huge difference in water conservation and soil erosion.

The Pot-in-a-Pot refrigerator—another invention of the Arab peoples in Northern Africa that has transferred itself to all parts of the developing world by means of foreign aid workers. Foreign aid/missionary organizations, such as Peace Corps and Mennonite Central Committee, are the honeybees of appropriate technologies, carrying good ideas from flower to flower around the globe. The Pot-in-a-Pot is so simple it seems impossible. Put a clay pot in a clay pot with a layer of wet sand in between them. That’s it. Too simple? Mohammed Bah Abba, a Nigerian scientist, apparently thought so. He “reinvented” this ancient fridge after much experimentation, and won a prize for the resultant patented zeer—a zeer being two pots with a layer of wet sand in between them. Food placed in the central pot will stay cool through evaporation. Water has to be replaced periodically; putting the zeer in a cool dry room, or setting it in a larger tub of water, will make it nearly trouble-free.

So the zeer has a thousand-year history—first it was invented, probably by women, because the man doesn’t care how the food gets on the table, just that it does. It was used without any fanfare until the tail-end of the twentieth century when a man got the glory. But I, as a woman, am not jealous or disgruntled about Bah Abba stealing our thunder—his “invention” has now benefited thousands of poor people and it could benefit you or me. And it’s always interesting to see how ideas boomerang through time and space.

The clay pot, by the way, has other uses that are known all over the world but especially in places where water conservation is a must for survival. Just as its evaporating powers can keep something inside it cool, it can also water your plants if you set it in the ground and keep it filled with water. Here’s what I’m wondering: could you combine the fridge and waterer? Perhaps someone who reads this can tell me. I’m just a khaki-thumb southern gardener with a muddled brain when it comes to science, but it seems to me that could work. Maybe you’d need three pots?

It’s possible you have used these technologies yourself. If not, try them. You’ll be aligning yourself with forces for change all over our beloved planet. With those who want to preserve the integrity of the soil, water, and air that we all share.

The Community Guide shows us that there are people—like you and me—who are trying to nurse our Mother back to health, trying to heal her gifted resources of land, air, and water, trying to retain and revert to older, gentler ways of utilizing those gifts. The book carries us through the four stages of development by looking at common scenarios through the eyes of the most naïve, and gradually revealing how such “little” people can move from accepting aid, to taking care of their needs, to educating others. They can “aprovechar” the tools they need—whether simple, like a plumb line or a pot-in-pot refrigerator, or complex and consciousness-raising, like cooperative community action—to fight the forces that threaten Pachamama, Astarte, Gaia, Terra, Devi, Durga, Demeter.

It’s their way—and ours—of saying. “Thanks, Ma.”