Turning a 1928 Bungalow into a Farmhouse and Other Misadventures

America in 1928 was a decadent place for some. Those who could afford the best had it. Prohibition meant that most everyone drank in secret; bathtub gin, rumrunners, speakeasies, and all that were commonplace. Al Capone was terrorizing the streets of Chicago. Flappers were kicking up their heels. Urban areas were already slowly becoming removed from their agricultural heritage, and many city dwellers were all too happy to swig their swill and marathon-dance their way away from farming.

But, also in 1928, a modest bungalow was built in West Wareham, Massachusetts.

It was a humble structure—probably no more than four real rooms, a bathroom, and an open porch when it began—built by immigrant Italian carpenters. A wood-fired cookstove likely abutted the brick wall in the kitchen. The “little kitchen” boasted an enameled cast-iron farmer’s sink and shelving. The bedroom was small, the bathroom probably outfitted with minimal plumbing. This bungalow sat near the crossroads of Main Street and Carver Road, an important intersection at that time, with railroad tracks not far away. A school was built across the street, indicating the town’s need to educate the neighborhood’s children.

That little bungalow would stand the test of time.

Over the coming decades, the bungalow would be tweaked, modified, remodeled, and expanded. More rooms were added—three, to be exact. The interior was paneled, wallpapered, and decorated to the glorious standards of the 1960s and ‘70s. The front porch was enclosed to make a three-season room. A mudroom grew up off the back of the kitchen like a mushroom, complete with a washing-machine hookup and a big closet boasting small stairs carefully crafted with a short person in mind. In the cellar, a workshop was created (most likely from the former makeshift bedroom of a teenaged boy). A clothesline went up in the backyard. A doghouse was lovingly constructed from scraps left over from exterior work on the house.

Much of this description is my own imagination at work, but I think it is likely correct. We bought this bungalow at the very end of 2011 and between things we were told at the closing by the sellers and our own understanding of the town’s history and our investigation of the cellar (being the good amateur archaeologists that we are), it’s probably a pretty accurate description of our home’s history.

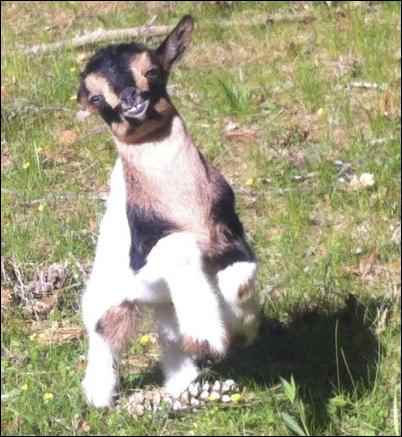

At the signing, we made a good impression on the sellers (two brothers who were selling the house because their aged mother—the former homeowner—was in nursing care in Vermont) when we explained that we already had a goat and wanted to keep chickens. One of them then smiled and mentioned that they’d kept chickens in the shed years and years earlier. I grinned and turned to my husband. The previous evening, when we’d been executing the final walkthrough of the house, I’d gone into the shed and my nose told me something. The aroma was one of ancient chicken poop. I called to consult Chris’ nose but his nose had no opinion, so I had chalked my impression up to daydreaming of the future. While in the attorney’s office, I pulled the photo of Sandy with Santa Claus out of my purse. The sellers seemed relieved to know that their childhood home was being bought by folks who wanted to preserve its integrity and were amused to know that we’d ensure its future as a small-scale homestead.

Winter in New England is hardly the best time to begin a major move. Thankfully, the winter of 2011-12 was one of the mildest on record. We had almost spring-like weather to assist us with moving all of our belongings out of a gigantic 13-room antique farmhouse and into a 1,000-square-foot bungalow. My Sainted Smudder, as she is known, had kindly parted with much of the family furniture when I took over management of that antique farmhouse that we were then vacating. Down-sizing required us to decide what to keep, what to sell, what to donate, and what to bring. Thankfully, many of our colleagues wanted things that would otherwise have gone to charity. We kept everything that qualified as a “family heirloom” or would otherwise hold its value, and everything that would be potentially useful in our new home. We schlepped things in the Escape and in the Rabbit. We enlisted our dear friend Michael and his pickup truck, who never wants to move our futon ever again (as he had moved it several times already), to haul things. We finally rented a U-Haul on the one day that the weather turned wintry that winter. We learned that I cannot move a piano (the limit of my ability to lift things) but we can move a glass-front antique china cabinet in sleet and freezing rain without quarreling (but never again do we want to undertake that task).

We arrived in our new home with lots of dreams but not much in the way of means. My husband and I had decided on this particular property for its potential: a small house on more than an acre of land that seemed well suited to raising goats, chickens, and a garden. It was hardly in a rural location, but it was secluded enough for our purposes and it was not far from work or conveniences like the grocery store and the highway to my Sainted Smudder’s house. At the time, we, like so many others, were feeling largely disenfranchised from a system that favored those with means over those willing to work for low wages. We wanted to do more for ourselves and less for that system.

Having spent a decade in the museum field, working in historic houses that had been built as hives of home productivity, I couldn’t help but compare our new home to those grand temples of domesticity. We had a pantry: it was a converted hallway with one set of shelves. We had a cellar: it had cabinets, but it was damp, despite the dehumidifier. There was no buttery. The attic was partially insulated, rendering it impractical for freezing anything (especially since our ancient coal-converted boiler meant the house had central heating). A healthy tree was growing out of the shed’s roof.

This place was going to need work if it was going to become my idea of a homestead.

The first part of our plan was to keep goats. Outside. We couldn’t afford to construct a goat pen immediately, but we already had a goat; that meant Sandy, still living in her pet carrier, moved into the mudroom with our new washer and dryer. I sat down with the map of our property and began sketching. One part of our yard would be the goat pen, but Sandy couldn’t live outside alone… not with a 30-pound fisher in the neighborhood. Another would be designated the kitchen garden, with neat 10’x10’ beds laid out according to a design I’d found in a book (The Complete Kitchen Garden, if you were wondering), full of healthy greens and roots and herbs, adjacent to the coop I had designed during a long meeting at work. Much of our woodlot would eventually go for firewood, once we installed the vintage Franklin stove my Sainted Smudder had offered us, and give way to an orchard and berry bushes and…

I’d been reading a lot about voluntary simplicity, homesteading, and history, so I began to think about ways we could use existing space and structures before contemplating any expensive improvements. We decided on specific uses for the extant rooms and features of the house. The small room that had probably once been part of the porch became our bedroom, and one of the supposed “bedrooms” became a studio for my textile work and my husband’s various art projects. The tiniest room in the house became the office, with its closet being dedicated to storing our reenacting gear. The cellar held great promise; I imagined the homemade cabinets (after a thorough cleaning and repainting) holding jams, jellies, pickles, sauerkraut, and squashes. I also mentally noted the location of every electrical outlet with the hope of acquiring a freezer for meats and garden goodies.

It quickly became obvious that we had not adequately prepared ourselves financially for the investment required to begin a proper homestead.

Armed with a few books on tightwaddery and employed by a fellow who knows his way around Swamp Yankee Thrift, I began trying to figure out Cheap Ways To Do Things. Our chicken coop was constructed from my awful sketches by a carpenter coworker for no more than the cost of materials, and assembled by a small army of capable colleagues who were willing to work for the traditional pay of food from the grill and beer. We adopted laying hens from friends who were relocating to round out our fledgling flock of (mostly male) Rhode Island Reds. Chris and I scored four free pallets from a nearby neighbor, and I filled them up with free aged manure from work. I used up old seeds and envisioned salad springing forth from these no-weeding-necessary garden beds. Our chickens envisioned a private spa and proceeded to dustbathe in the spaces between the slats in my “raised beds”. They devoured my sorrel and uprooted my transplanted herbs.

We had all of one lettuce plant and a fistful of dill for our first harvest last year.

Autumn rolled around, and Sandy was still living in the mudroom. We kept meaning to build her a pen and find her a friend. To be fair, we’d dealt with a number of minor crises since acquiring the Bungalow; the greatest of which came to be known as the Great Mold Crisis of 2012. Unbeknownst to us, the basement had flooded and created a haven for fungus. It took over Chris’ son’s room (which had once been the cellar workshop and previously the makeshift bedroom): scaling the furniture, assaulting his clothes, and invading every porous surface available. Two days of bleach, vinegar, Lysol, sunshine, fresh air, and three trips to the dump later, our basement was empty and de-molded, leaving us feeling somewhat discouraged about the future ability to use the basement for storing food. But despite that setback, we had happy and healthy free-range chickens; a happy housegoat who loved drinking water from her cup at the sink; and the best of intentions.

For all my careful planning, things somehow never go the way I think they will. I’ve dubbed our lifestyle “homesteading-by-crisis,” given how often it’s a crisis of one sort or another that shoves us into action. We adopted a second goat in November before he went to auction since Chris couldn’t stand the idea of the friendly little buck possibly going to slaughter. That meant we had to build a pen, and in a hurry. One Saturday afternoon and $250 later, Eureka came home on Chris’ lap and moved in. Sandy joined him, much to her rue and dismay.

While we were discouraged that we hadn’t achieved much in the way of garden produce, Chris and I were very pleased that Year One in the Bungalow had resulted in the keeping of chickens and outdoor goats. We had even sold eggs to some of our coworkers! This was a major feat in our thinking, and we were pleased to start planning for Year Two.

What we hadn’t anticipated in Year Two, or at all, really, was Maggie.

I’d had designs on adopting Sandy’s baby sister for some time, but I didn’t actually think I’d succeed. Just six months after delivering Sandy as our April Fool’s surprise, Tulip threw twins (again) and they weren’t likely to be useful to our breeding program at work. Tulip—ever the coy mama—kidded while I was at lunch one Sunday in October: a mixed bag that I named Marshall and Maggie. John, my boss, didn’t want to keep them, and I kept lobbying to adopt Maggie. He kept saying, “No.”

Just after we closed for the season in 2012, Maggie got her head stuck in the fence. A buck of a different breed managed to open the gate separating their pens, and, of course, Maggie was in heat.

Two days later, Maggie moved into the new goat pen in our backyard.

We spent the winter thinking about what we would do in the coming year. Chris and I concluded that 2013 would be the year of a garden and bees. Michael, of futon-moving fame, had found us a free goat shed and a free freezer. I continued to imagine beautiful canned produce from our garden filling the shelves of our cabinets and buying into a meat share so that we could have better food than that available at the grocery store. I made the mistake of asking John what it would cost us to buy half a pig from him at some point in the future and promptly found myself the proud owner of a whole pig and a lamb just come from the slaughterhouse.

This is not exactly how I imagined homesteading.

I had envisioned a slow, deliberate move away from commercial food and toward doing more for ourselves. I had imagined a little bit at a time. I had imagined planning, rather than action-inspired-by-emergency. But homesteading is what it is.

My grandmother—an avid gardener and one of my truest inspirations in life—died this April, two days shy of her ninety-seventh birthday. I received a small inheritance when she passed, which I turned into a fence for the garden (lest the chickens wreak the same havoc as last year), plus seeds and plants and tools. As I cut the garden beds from the grassy turf and shoveled manure onto them, I could feel her smiling at me from beyond. I knew I was finally stitching together her dreams with my own and making good on the promises we’d made to the sellers when we bought the house. Berry bushes and orchard trees were in our future, and I knew it. I calmly swore off homesteading-by-crisis.

One fine morning about two weeks later, I looked out the bathroom window and started screaming for Chris to come quick.

There were too many legs in the goat pen!

We had gone from three goats to five overnight; Maggie and kids were well. We were suddenly thrust into the wild world of milking a not-quite-dairy-goat and bottle-feeding two tiny terrors while trying to work full-time and sow garden seeds and prepare for bees. Gandalf and Galadriel, our new kid goats, followed in their Aunt Sandy’s hoof-steps and had to come to work with us for their midday feeding and brought great joy to our coworkers as they capered around the break room. Maggie turned out to be an excellent project-milker, despite her very small stature and therefore very small output. We relished every drop of our own goat’s milk in our coffee, our scrambled eggs, and our first cheese.

Since Chris couldn’t bear to part with the first offspring of Withywindle Farm, we sold Eureka, wethered Gandalf, and decided to keep the babies: Gandalf to train as a pack goat and Galadriel to breed for comparison purposes. I’ve been poring over Pinterest with plans to fully update our tiny homestead pantry/freezer area at the foot of the cellar stairs. There’s one ripe tomato out in the garden, along with a number of green peppers that are almost ready to be chopped up and frozen. We’re up to our ears in cucumbers and basil. The bees will just have to wait until next year.

Eventually, we’ll get around to taking down trees and expanding the homestead, since our Year 3 and Year 4 plans include that wood stove, those berry bushes, and that orchard. We have the chance to buy a couple of Alpine doelings at a bargain, which would up our milk supply significantly while allowing me the opportunity to keep working on my San Clemente Island (dairy) goat project while still having milk in quantity.

In the meantime, I have another freezer to set up in my cellar before we buy half a cow and a new goat pen to build. Our bungalow may never have been intended to be a homestead, but it puts up with all our crazy antics. It might not be a farmhouse yet, but it’s well on its way, whether or not that’s what its Italian housewrights intended in 1928.

Post-Script

With homesteading, whether by crisis or careful planning, there always comes heartbreak. Our darling Galadriel, sweetest and kissiest of goats, died on August 25, just four months and a day old. Losing her thrust us into the typical self-questioning and self-criticizing that goes on among farmers when something has gone wrong. Did we give her too much grain and cause polio? Was it a mosquito-borne infection? What could we have done differently?

But the worst thing we could do is to give up. I’ve already paced off the fence line for the Alpine pen and jotted down prices for materials and agreed to bring them home this fall. Chris has been reading up on training pack and harness goats; he and Gandalf can work together and take their minds off the loss. I’m still admiring the basket of cucumbers and summer squash from our garden, cursing Peter Rabbit for his forays into our salad greens, and hoping that the fall crop of peas might end up somewhere in our kitchen instead of in the rabbit’s stomach. Even if our efforts aren’t “profitable” yet, we’re still learning and still growing. There will always come crises. There will always be loss.

But give up? Absolutely not.

lovely story! I really enjoyed it. So sorry for the loss of Galadriel. Heartbreaking. Congrats on all your efforts and learning skills, I wish you well in the future!