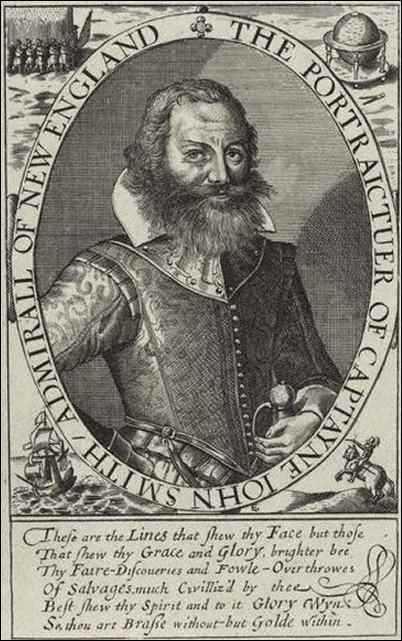

Captain John Smith told the English colonists under his sway “he who shall not work shall not eat.” It was a Biblical injunction, stated to discourage the Jamestown settlers from the happy notion that precious metals abounded in the New World and that pickings would be easy. Smith was right. There was nothing easy about homesteading in the new, unnamed territory.

He who shall not work shall not eat. Words to hack, hoe, and hew by.

Not that homesteaders have ever needed much extra incentive, Biblical or otherwise, to acquire a patch of land, tend it, and live in harmony with nature, whether or not they choose to live in harmony with or isolation from their fellow humans. Homesteading, in the 1600s as in the 2000s, mainly requires guts and a certain attitude.

The attitude. Very few people, proportionately, voluntarily left the Old World for the New, and most who did were peculiar, or remarkable, or both: ex-convicts, members of minority religious sects, people of the wrong color or genetic code, people who couldn’t stand authority, people who were not willing to move with the common herd, people who were starving, people who lived in fear for their lives in their homelands.

The guts. This is a stark requirement for those who choose to carve a completely self-sufficient life out of a raw tract of scrub pine or a square of desert or a precipitous mountainside. Homesteading is not for sissies.

So how did American homesteading evolve from the necessary toil of colonists and risk takers, to an incentive-based government program, to a haven for a recent crop of homeschoolers and eco-diggers?

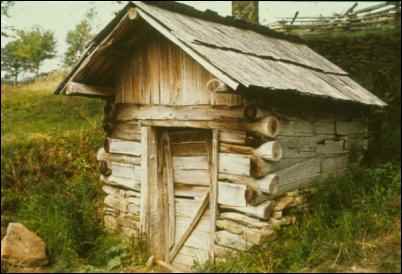

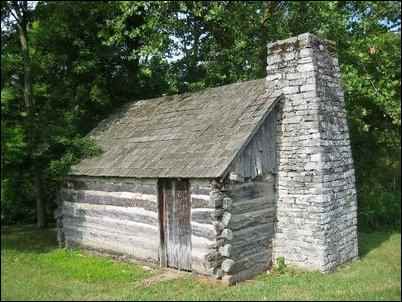

Going back to the beginning: in his book Everyday Things of American Life 1607-1776, William Chauncy Langdon writes that the Jamestown and Plymouth settlers started with dwellings of tarps and lean-tos, “somewhat like the shelters of the Indians. The Indian name of wigwam was soon transferred to them…because both Indians and Englishman alike were availing themselves of the simplest way of building with what material was at hand.” Naturally, such structures did not survive, though there are many log homes of later vintage that can be seen on display, and a few in use to this day. But the sapling branched, mud-daubed lean-tos have long since reverted to their natural components.

First principle: if you don’t bring some implements to get started, it’s not homesteading; it’s camping. Thus even our earliest homesteaders were bound by the needs of the cash economy.

The “camping” phase was over once the first substantial tree was felled with an ax.

John Smith’s rule “he who shall not work shall not eat” was reality. Smith worked side by side with his colonists, and claimed that the labor brought “delight to heare the trees thunder as they fell.” Remembering that these were strictly religious folk, Smith’s diary records that anyone who called out “a loud othe” when the axe “blistered their tender fingers” was punished by having “a canne of water powred down his sleeve” – a serious disincentive to swearing in cold weather. The felling of trees served a dual purpose, as lumber was a sought-after commodity in the Old World and colonies were there to serve the needs of those who sent them, as well as to provide a living for the newcomers. That was the first, small, wave.

So you’ve just arrived in America, on the east coast, in the spring. You’ve survived many weeks on troubled seas, a landscape unfamiliar and terrifying, in quarters that breed disease and madness. Some of your number, perhaps of your own family, did not make it to landfall in this odd new place you will call home for the rest of your natural life. You’ve packed tools you hope will be useful, things you can’t easily make for yourself, like a spade and a hammer, cooking pots and sharp knives, and a gun to shoot game and invading hostiles. You have the clothes on your back and a few more, perhaps, and maybe you’ve brought along a spinning wheel or a small loom to produce more when you have time. You have yet to experience the extremes of climate that America has to offer; the weather is a little chilly right now, but you have no idea how the snow can pile up to the window sills and later, how blazing hot it can get. No idea of the torments of mosquitoes, fevers, swamps, deserts, sharp rocky mountain peaks, rivers wide like the sea, savage human foes, wild animals and poisonous vipers on the prowl – all that lies ahead.

You are in the middle of a virgin, or old growth, forest consisting of a total canopy of branches overhead, and a shaded floor undisrupted by weeds and grass. Therefore your greatest resource is – trees. You’ve come from a culture where such a vast abundance of trees is merely legendary. You have never built, possibly never seen, a house of logs. But you will build one now.

The bad news about log construction is that every log is unbelievably dense, awkward and dangerous to set in place. The good news was that very few are needed to complete the job and they form both an inner and an outer wall that, with mud as a “daub” they are largely impervious to rain, sleet, snow and the harsh rays of the sun. Such a structure rises quickly – with help. But the dangers are ever-present. How many colonists had crushed limbs and digits from the rigors of log construction, not to mention those blistered and possibly lost fingers from hacking down mighty trees with small hand tools? And with medicine still in the dark ages, how many died from gangrenous wounds before their lives in America ever really began?

Once the cabin is built, you have shelter and land that was roughly cleared. Among the provisions you will have brought with you would be seed. A crop had to be produced this year without fail – he who shall not work shall not eat.

Early European settlers brought wheat and barley. They quickly learned about corn from the Indians, and Johnny cakes and whiskey soon followed. Beans were another staple. As more settlers moved in, some with greater financial means, fruit trees arrived. Everything grew gleefully. America, if not full of gold, had golden soil.

The first half of the United States, enough territory to establish us as a world power, was grabbed by a few small boatloads of hardy, ambitious folk who wanted more for themselves and their children than a brutish life under the sway of king and church.

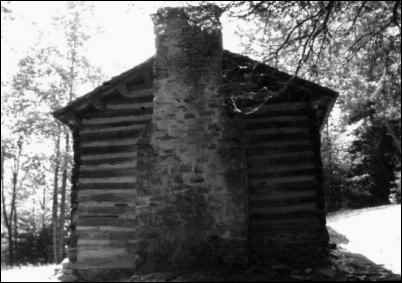

The fiercely independent, often bitter, Scotch-Irish took a liking to the isolation of the Appalachian region. These mountains, stretching from Georgia into Canada, were the first major barrier to settlement. So insuperable did the tree-covered peaks appear that an early proposal for a name for our country was Appalachia, or Alleghenia. Those who homesteaded within their forests were not primarily farmers. They lived in cabins unseen by neighbors and unvisited by preachers. They hunted, they made parlay with the Cherokees, and when that didn’t work, they fought them and the score was generally about even. Some, like the legendary Melungeons, were left-overs, perhaps Spanish mixed with Cherokee, from the earliest days of exploration. The settlers of the southern Appalachians made their own drink, sang their own songs, had their own quilting style and invented their own religion, in some cases involving the handling of snakes. They favored a double room house with chimneys at both ends, rude and rarely ornamented. Southern Appalachian folk were able to survive in rude shacks often accessible only by crossing log bridges and assaying steep trails, well into the twentieth century. Even today there are people who live “back in the hollers” pursuing life as they please and converting grain into liquid fire.

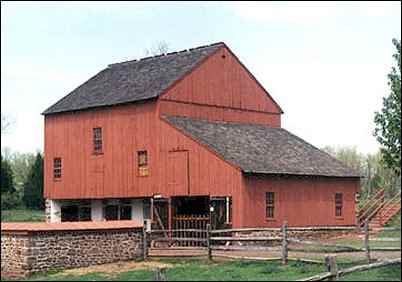

Germans, veteran field cropping farmers who took the long view, sought open spaces and built solid houses and multi-storied barns. Their properties were kempt and organized. They liked Pennsylvania and put the stamp of their culture on it, including the lifestyle of the peculiar Amish. Like most settlers, the Germans exploited the quick to-hand resource; they cleared the land of its trees and used the timber to throw up log and board shelters. “Schaffe, schaffe, Häusle baue” (“Work, work, build your little house”) was their motto. They favored houses with central chimneys, and had the very practical notion of constructing on a hill. At the top of what came to be called the “bank house” was the living quarters and underneath, the two-level barn. This allowed them to get farm equipment inside more easily. As they prospered, and they usually did, they build new houses of stone or covered the old logs with elaborate siding. Many original German houses in Pennsylvania and elsewhere are still occupied.

Scandinavians were here before Columbus, since Leif Erickson famously made landfall in Greenland around the year 1000. They tended to the familiar northerly climes and painted their homestead buildings red, as at home, so they could be found in the snow. The life-embracing French fanned out along the Mississippi River where trapping and fishing offered a living within the natural landscape, requiring little alteration. Though they often left the land much as they found it and traveled seasonally, the French established forts from Quebec to Louisiana that formed the basis for many port cities. The Spanish went south, always seeking sunny regions where they could enjoy the fruits of home and continue looking, mostly without success, for gold.

No one was thinking much about preserving forests or keeping the waters pure. But the immigrants were still few in number, and their incursions were minor, barely a blip on Mother’s Nature’s screen compared to the physical degradation and overpopulation of the places they’d left. Daniel Boone was our quintessential first homesteader. From the Carolinas to Missouri there are signposts, the occasional cabin, and more than one town attesting to Daniel’s presence and adventuring spirit. His family came to Pennsylvania as part of the despised sect, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and dissented from the dissenters, forcing a move to North Carolina where Daniel’s father homesteaded less than 30 miles from where I live, in the Yadkin River region. When school children think of log cabins, the Boone name leaps to mind. But Boone also created trails that became roads, moving on to follow abundant game and good farmland.

Boone was also an eco-visionary, if a self-motivated one, who noticed that game got scarcer as people moved in; he kept hacking his way west to find the big kills. Everywhere Daniel decided to homestead with his wife and a passel of kids to share the chores, he started with a hunt for salt. Without salt, meat couldn’t be preserved. Without the ability to preserve one’s kill, it was “camping” again, not settling, not homesteading. Everywhere Daniel and those like him went, pots, pans, spinning wheels, tools for sewing and making shoes, tools for repairing weapons and fashioning furniture, all got dragged along. Oxen had to be imported. Horses were not indigenous to the east coast. Letters to the world left behind got lost or took months for a response. There were few books, the most prevalent on beings the family Bible keeping a record of births and deaths. No how-tos. No recipe books. No clothes patterns. No entertainment. No neighbors. Few medicines. Limited foodstuff.

Homesteading meant doing without. But it was doing without with a difference, because the big prize, a piece of the good earth, had already been won. All that was to come sprang from the deeply American conviction that a man’s homestead is his castle.

The colonial phase of U.S. history lasted about one hundred fifty years. Within that span, all of what we call the East Coast and some of the Midwest was occupied, and a few intrepid souls trekked all the way to the Pacific. Both Native Americans and large numbers of African slaves were made subject to the whims of whites, and a cohesive nation was gradually forged out of war and a grand vision. Following the early colonists dispatched by wealthy businessmen (also known as second sons who themselves would need land) came the adventurers, the indentured, the entrepreneurs, and the religious. Arising out of crowded, restrictive, intolerant nations, they all shared the same burning desire: land, land, land. Land in Europe was in the hands of the gentry and this was deemed the Lord’s will. Common folk might prosper, but could not have a freeholding.

So for some, the dangerous voyage, the back-breaking labor, the path-finding and the prayer paid off. In the New World, a family could live free from the yoke of tyranny. The key to freedom was property.

If a person could have his own piece of the earth, what could he not do? And to whom need he be answerable?

The History of American Homesteading, Part 2: The Little Cabin at Sinking Spring