Let’s be honest. It really doesn’t look like something you’d want to eat.

Line your driveway with it, sure. Throw it at a groundhog, definitely.

But eat? That lumpy brown thing with EYES? I don’t think so.

In my twenties, I learned how to grow potatoes in a sack, and came to love their lumpy, newly excavated appearance and earthy odor. But it was a long time after that before I learned the twisted, tragic, ultimately triumphant tale of the humble spud.

Let it be said, my first introduction to the potato was hardly unpleasant. Mashed, boiled or baked, it was a mainstay of post-World War II nutrition in all Western countries. In our southern home it was a requirement on the supper plate. In the North Carolina mountains, my husband-to-be, then a mere child whose red hair and surname announced his Celtic origins and his innate kinship with the potato, believed that there were only two varieties of potato: the red and the Arsh. Years later he realized that this latter designation was Hill-speak for “Irish.”

But long before the potato became America’s favorite starch, and centuries before it made it to Ireland, South America alone cherished the humble spud.

The History of Potatoes

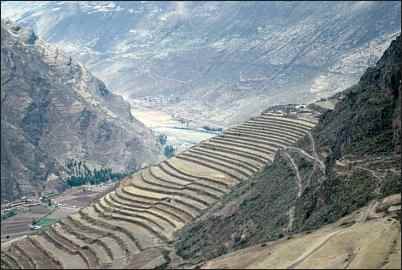

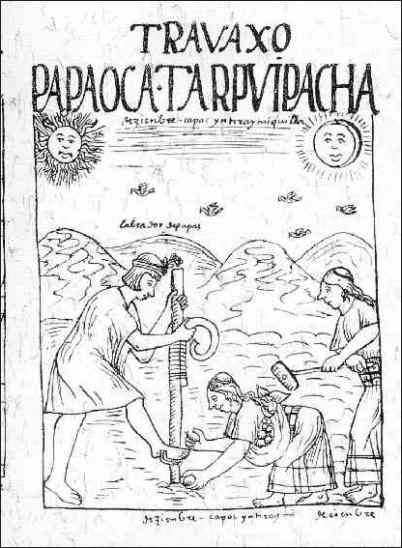

The Incas, whose civilization prospered for hundreds of years and vanished as soon as the Spanish came to plunder, revered potatoes. They lived in the high Andes Mountains with freezing temperatures and scarcely a drop of rain all year round. Their potatoes were purple, blue, red or yellow, small and gnarled. They forgave the tubers their ugliness and invented ways to store them for years at a time, a hedge against famine and a great snack for a trek. Though we do not admire the Incas for their ritual child sacrifice, in most ways theirs was an enviable society. Their wealth in gold was so abundant that no one tried to guard it, and though they never invented the wheel, they had a road system that was so well constructed and far-flung, it’s almost as if they had envisioned automobile travel. It is believed that they cultivated up to 3,000 varieties of potatoes in terraced beds in the highest Andean peaks. In deep trenches where the bottom layers of soil replicated warmer climates, with stair-step levels to facilitate irrigation, these sandal-footed horticulturalists developed potatoes suitable for every region of their empire, which comprised most of the western coast of the South American continent.

The Inca product chuñu was the world’s first “instant potatoes”—frozen spuds were trampled on to get rid of excess water, then dried in the sun to make potato flour that could be stored for years. All they lacked was a catchy jingle, and it’s possible they had that; since they lacked a written language we’ll never know. To say the Incas worshipped the potato would probably be stretching a point, but they did put the starchy lumps in the graves of their dead—what could be more reviving for that final journey than gnawing on a potato?

The Incas were conquered by the Spanish who fervently believed that God wanted them to kill anyone they couldn’t baptize, or, if necessary, baptize them and then kill them. Assured that the Incas were mere savages compared to themselves, they made few efforts to preserve or even examine Incan culture, and so the high art of potato cultivation was lost. Today we are sure of only about 40 of the 3,000 varieties that once flourished in the Andes.

At this point in our story, the humble spud is still in Inca. So how did it get a ticket out? It seems to have sneaked out of Peru under an alias: batata, the Spanish name for ipomea, or sweet potato.

The Spaniards brought the batata (later renamed papa) to Europe around 1570, using it only to feed people in hospitals. But most healthy people found it hideous, and anything hideous must be a tool of Satan. The educated classes were sure it was to be avoided because it is of the family solanum which also includes the toxic deadly nightshade. Most Protestants would not eat it because it was not in their Bible, and Catholics only consented to its consumption after a priest had blessed it. This was not an auspicious beginning to the potato’s life in the so-called civilized world.

Europeans have long been meat-obsessed, convinced that without a slab of cow or a joint of pig on the plate, they will surely perish. It took Sir Walter Raleigh, who was greeted with consternation when he brought back potatoes instead of precious metals from the New World, to demonstrate that the spud is as good as whatever it’s eaten with. He started a potato-and-beef-gravy craze that swept through the elite classes with a fervor unmatched until the invention of the iPad. Thomas Jefferson, on his side of the ditch, also championed the potato. But in the main it languished for a couple hundred years as food for peasants and fodder for swine.

By the late 1700s, the Irish, not exactly by choice, lived on the humble spud—before it killed them. They would be somewhat justified in believing that the potato was foisted upon them as a way of wiping them out. It has been referred to, often, as an instrument of British genocide.

The Irish in question were those who, by opting for the wrong politicians and the wrong religion or by incautiously ignoring the whole thing, were living in on a muggy windswept island in crowded conditions and dire poverty. They had once, it is believed, lived on oats, but climatic conditions had made grain cultivation impossible. So they welcomed the starchy, vitamin-rich tubers, which, legend has it, tumbled off the defeated, listing vessels of the Spanish Armada, bringing bad luck with them as they hit the green shores of Erin.

The Irish saw not only the potato’s nutrition potential, but the energy gain in husbandry, requiring no back-breaking labor at all. They literally threw the spud eyes into what were called, possibly satirically, lazy beds—banked up hills of earth and nitrogenous waste with ditches at each end for drainage—of any size according to the size of the farmer’s plot. This left the Irish free to fiddle and frolic (as the English sneeringly supposed), able to scoop food out of their compost once a year, store it underground for the coming year, and fill up the lazy bed again come spring. This happy marriage of filling mono-diet and lackadaisical husbandry held together for many years.

Until 1845.

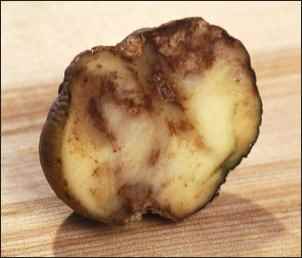

At that point, the Irish had, by most accounts, forgotten how to cook anything but the potato. When the mood struck them, they would eat the tubers raw for convenience. But most plants, when mono-cropped for many years, will begin to develop dangerous anomalies. The Great Starvation or the Potato Famine was the result of not one, but several blights. Potato plants would appear to flourish and two weeks later, melt into a brown stinking heap. The fruit was leprous with dry rot or putrid with wet mold. In fewer than five years, the population of Ireland dropped by half, and the lucky ones who did not starve were off to America to escape death. Not just their own deaths, but that of their culture.

The Irish were unwelcome in the U.S., and the potato was no less so at first. Spuds were for pigs and the Irish. But in time, the humble spud proved its worth. Despite its bad reputation, it was known that sailors who ate potatoes did not develop scurvy. Thus, despite the negative experience of the Irish, some thought that the potato was a food worth cultivating, and the ideal conditions—mainly, plenty of wide open spaces—existed in the U.S. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the legendary Luther Burbank had developed a disease resistant potato. He sent it to Ireland but also carried it west. Idaho farmers embraced the Russet Burbank potato and opened their vast lands to its growth.

Danish nutritionist Mikkel Hindhede influenced his government’s food policy during World War I by advising Danes to get rid of all their pigs and most of their cows and eat what they’d been feeding the animals. In this way they staved off famine and survived the war better than their neighbors. Hindhede, suspicious of the accepted wisdom about the necessity of eating meat, was convinced that potatoes contained sufficient protein so that, combined with some fat such as butter or margarine, they could be a successful mono-diet. He himself ate nothing but potatoes for three years with no apparent ill effects, and lived to be eighty-three. This kind of research elevated the lowly tuber and brought it onto more middle classes tables in the twentieth century.

Having sufficient acreage in the fields of Idaho and the Midwest to rotate potatoes with other crops has kept blight and rot from developing, and newer hybrid types have carried the development of the humble spud happily into a new century in which even the most elite of us will occasionally succumb to the siren call of the curly fry or the baked potato buffet. The modern potato plant is leafy with delicate yet deadly blooms, while its fruit is big, heavy, uniform in size and, though largely tasteless, can be eaten raw as long as no green can be seen. But take warning: the “Irish” potato of today is high in glucose and not recommended for diabetics. Mikkel Hindhede and those to whom he fed potatoes for experimental purposes were hardworking farmers who could process glucose rapidly through exercise. We who do little physical work will soon become—you got it—couch potatoes, if we eat a potato-laden diet.

The word “spud” by the way, probably derives from the Germanic word meaning “spade”—and would originally have referred to the tool used to sow the potato eyes (I still find the notion of a tuber with eyes creepy), later to the act of sowing and thence to the fruit itself. Here’s a reference to the word spud from “The Ruined Maid” by Thomas Hardy (1840-1828) about a young girl who left home and turned to prostitution:

“You left us in tatters without shoes or socks,

Tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks*;

And now you’ve gay bracelets and bright feathers three!”

“Yes: that how we dress when we’re ruined,” said she.

*weeds

The Incas used a foot spade to plant potato eyes, and the Irish a stick or occasionally a simple spade. I say “simple” because the Irish who lived on the potato existed outside the cash economy almost entirely. That explains why a girl might prefer lying on, rather than digging, a lazy bed. Oh, yes, the English had more than one joke about that. But all in all, the English lost the Irish and we gained them, and strengthened our own culture thereby.

I mentioned that potatoes can be grown in a sack. It’s a great way to have a crop to brag on while, like the Irish, having done almost no work to secure it. Don’t need acreage—a sunlit patio will do. I read about this method of spud culture in a long-ago issue of The Whole Earth Catalog. Though this process has become so well known that it is now possible to buy potato bag kits, I think the method I learned is the best. And it works!

In the cool of early spring, fill a large burlap sack with potting soil, peat moss, plenty of fertilizer and moisture-retaining mulch in about equal parts. Seal up the open end. Lay the bag on its side on the ground where you want it to remain from sowing to harvesting. Spuds will enjoy full sun, but not very high (80-90º) temperatures. Cut holes in the top side of the bag, and into each hole insert potato pieces that you have cut and then dried for a day. Each piece should have 2 or 3 eyes (try not to think about the potatoes looking at you). I recommend red potatoes which have a lower glycemic level and more flavor, especially when harvested new. You can be haphazard or neat with your holes, but keep them about 6 inches apart.

No other fussing is required, though if you’re having drought you can sprinkle water on your bag, but do not douse. Potatoes like misting. A few weeks after the plants flower, you’ll feel the potatoes in the bag. So the next step is—voila!—harvest and eat.

If you want to try something different, be patriotic! Try a July mix of reds, whites and blues (now available in organic/whole-food stores). During the harvest, play the pan pipes and the fiddle to honor the international ancestry of the humble spud. And to bring it all back home, strike up a rousing pipe-fiddle-banjo rendition of Yankee Doodle.