Chickens are one of the easiest forms of livestock to raise and can be raised in many areas, including dense suburbs and some even raise chickens in the city. Raising backyard chickens can be very productive too: they give you eggs for breakfast, they can give you meat to eat, you can breed them to make more profit (or just have more chickens). Not to mention they also make great pets.

You may ask, “Why would I raise my own chickens when I can buy eggs for $1.72 a dozen, or just get a roasted chicken at the store?” I won’t get into too much, but the main reason to raise your own chickens would be life on “factory” farms. You can just do some quick research online about commercial chicken farms, and learn all about the bad conditions on these farms, and the negative effects they have on the chickens’ health. It is a fact that free-range eggs are more nutritious for people, and a lot more humane for chickens. If you buy “free-range” eggs at the store, you’ve still got to watch out because “free-range” doesn’t necessarily mean that the chickens are running free through green fields. Research that, too. The other overall benefits are that you know what you’re eating and the joy you get from raising backyard chickens.

Trust me, chickens are easy to raise, they’re fun, and you can even find ways to go cheap. Coop construction can involve many recycled materials. I have put many hours of research into raising chickens, and I also have my own flock of five, which is small, but still gives me good experience. My flock contains three Buff Orpingtons and two Speckled Sussex. I have gone through many chicken-raising processes and look to share my knowledge all in this one article.

Starting Out with Chickens and Feeding

Before you even start, you should consider what kind of chickens you want. What do you ultimately want the chickens for? If you want to raise your chickens for meat, you want breeds good for meat; if you want eggs, you want breeds that lay well. There are even ornamental breeds for people who mainly like chickens as pets. Along with that, for each breed of chicken, there is usually a “bantam” version which is like a miniature chicken. My birds are dual-purpose, which means they are good for both meat and eggs. There are other factors that have to do with egg-laying like broodiness. There are resources on the internet to find breeds that fit your purpose.

To start out, you want to be prepared. Even though young chicks (if that’s what you start out with) won’t be in the coop right away, it’s nice to have one already prepared (I will get more into coop building in the next section). If you buy chicks you will need a brooder, and if you hatch eggs you will need an incubator. You can also just buy full-grown chickens.

I bought my chickens when they were three weeks old, but some people may prefer to buy fertilized eggs and start from scratch with an incubator. If you are already established and want to raise more chickens you may need an incubator for that, too. To check if the egg is fertilized, there’s a process called “candling”, where you hold a light up to egg, allowing you to see the yolk inside. This is something to do more research on your own if you’re interested.

Now, I already mentioned chicks don’t go right into the coop, and I also mentioned something called a “brooder”. Chicks need to be kept at a certain temperature at different stages or they will freeze and die. A brooder is basically a little heated pen that you keep the chicks in until they’re ready for the outdoors. It doesn’t have to be anything elaborate; mine was a plastic bin with pine shavings on the bottom and a 250-watt infrared heat-lamp above it. The heat lamp was on a string so I could lower or raise it to adjust the amount of heat in the bin, which I measured with a thermometer. Also in the brooder was food, water, and a mini-roosting bar. The type of food is also critical to each stage, and I will go into more detail about that later.

For temperature, this is how it works, give or take:

- Week 1: 90-95 Degrees F

- Week 2: 85-90

- Week 3: 80-85

- Week 4: 75-80

- Week 5: 70-75

- Week 6: 70-75

- Week 7: 70-75

- Week 8: 65-70

- Week 9: They’re good to go for whatever temperature.

Another way to tell if the temperature is right is by seeing how the chickens react to the temperature. If they’re huddled together under the light, they’re too cold. If they’re all on the sides trying to avoid the light, it’s too hot. If they’re scattered around normally, they’re just fine.

Another thing you want to do is change the bedding frequently because the chickens are more prone to disease at this stage. I changed my pine shavings every two days. You can tell if a chicken is sick mainly by how it acts, and the poo (there is actually a poo chart on the internet you can look up for reference). Some people use medicated feed, and that’s up to you. It prevents chickens from most diseases, but I never used it because I believe it’s good to have them build up a resistance. The water should be changed daily.

I have already mentioned that food depends on the stage, and it’s based basically how much protein they should have:

- 0-10 Weeks: Chick starter, 10-20% protein, higher in meat birds.

- 10-18 Weeks: Grower feed, 15-16% protein.

- 18 Weeks or when chickens begin laying: Layer feed, 16% protein plus added calcium for laying. This isn’t necessary if you’re raising meat birds.

Free-range chickens can technically survive on their own without being fed. When outside, they will scratch around in the dirt and look for worms, grubs, ticks, and other goodies. They will also eat a variety of plants. Chickens will eat nearly anything, even if it’s not edible. You shouldn’t give them anything that you wouldn’t eat, but they will go nuts on slightly tainted or ugly foods from either the kitchen or garden. This makes good use of those ugly looking tomatoes or half-eaten lettuce from the garden. There is a “treat chart” online, which tells you what’s poisonous to chickens, and what they really love. I work at a produce market, so I bring home ugly produce that we would normally throw out, and the chickens go nuts over it.

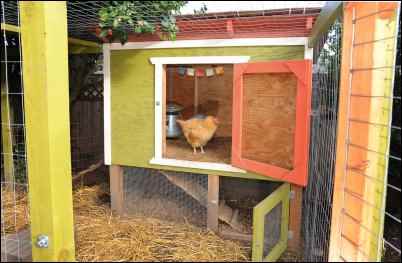

Once the chickens are ready for the outdoors, they should have a nice coop to move into. You can either buy a coop, or build your own—which I would highly recommend. Building your own chicken coop is a lot of fun, not to mention a whole lot cheaper. You can build to your standards and it doesn’t require a whole lot of skill. Chicken-coop plans are all over the internet for free. Something else you can take into consideration is using recycled materials. I never did this, but I sort of wish I did. Using recycled materials makes the process cheaper, you can get really creative, and it’s also eco-friendly.

The basic requirements for a coop are that it has enough space (rule of thumb is about four square feet per chicken), is draft-free but well ventilated, and has a roof, nesting boxes, and roosting bars. I learned that ventilation is key, especially in cold weather because chickens produce a lot of moisture and odor; you can never have too much ventilation. Some other things to consider is having the coop off the ground (keeps out critters and is a bit warmer), having an attached run, and having room for feeders and waterers.

As far as bedding is concerned, I recommend pine shavings, but you can also use stuff like straw and grass clippings. A bedding method I prefer is a called the Deep Litter Method (DLM). This is something you’ll want to do a little research on, but to summarize, DLM is basically having a mini-compost pit in your coop. You start out with about four inches of (ideally) pine shavings, and every week or so you stir the bedding and add another layer. You only have to change it out about two to three times a year, and it produces very little odor along with a bit of heat. This mixture is nice to mix in with the garden compost pile.

A run, as I have mentioned as something ideal, is an outdoor pen for chickens. I have two built into my coop: one which is roofed, and another that’s open. A run is nice if you live in an area where you can’t free-range your chickens. Even if your chickens are free-ranged, a roofed run gives them space during bad weather. During winter weather, you can add plastic to the sides to make it an extended indoor space. If you live in the suburbs and/or live in a predator heavy area (as I do), you may have the chickens go into a run instead of running loose. I actually “partially free-range”, where I let my chickens out with me when I’m outside). Chickens should have ten square-feet each in the run.

Two other things your coop needs are nesting boxes and roosting bars. Hens prefer to lay in confined areas, and you want them to lay somewhere you can easily access the eggs. This is why you build nesting boxes, which are small boxes about 12”x12”x12”, ideally off the ground. It’s also nice to have them extend outside the coop so you can easily open a door to get to your eggs. The pine shavings in these boxes should be cleaned about weekly or sooner if needed. Roosting bars are where chickens sleep. They prefer to be off the ground when they sleep, so you have to install bars inside the coop about 8-12” off the ground. I used 2x4s in my coop and they work just fine.

Raising Backyard Chickens in Winter

Most breeds of chickens can handle the cold weather in many areas just fine. Some people panic when it gets cold, but there really is no need. You don’t need heat, and extra light is something that’s optional. The biggest pain may be keeping the water from freezing, but a heated waterer solves that.

As I said, extended light is optional. Chickens need about fourteen hours of light a day to lay eggs. Days get shorter in the winter, and if you want eggs you have to add light to the coop. The light should be on a timer and go on a few hours before sunrise in the morning and a few hours after sunset. I personally don’t do this because my chickens are more pets to me than sources of food so I buy true free-range eggs over the wintertime. Some people also say it’s natural for chickens to have a break.

The two things that go beyond common logic and are very important to remember are not to add heat and to have good ventilation. The problem with heat is that chickens can die from a sudden drop in temperature if it were to go out for some reason. Besides, they don’t need it; they just need a draft-free space. You should also keep the ventilation open. People think that since it’s cold, all the vents should be closed. This is wrong because people forget about the moisture chickens give off. They can get frostbite from the moisture added to the cold. Plus, the DLM needs air.

Back to the idea of wrapping the run in clear plastic: this is ideal because it will keep the draft off the chickens, and also keep out snow. Chickens won’t step foot in snow. The plastic sides, along with the roof, will give chickens comfortable outdoor access.

Raising Backyard Chickens for Meat and Chicken Breeding

I combined these two topics because I will only touch on them in this article, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t much to know. Right now, I just raise my own chickens for eggs, so I have no experience in these topics, but they are important to mention. Most of the info I’m going to give is summarized from the internet, but if you’re considering doing either of these things, you’ll want to do your own research.

Now, for meat production, a common misconception is that when your chickens are done laying (around three years), you can kill your chickens and eat them. You can do this, but the meat will be tough. Meat chickens are typically slaughtered well before the laying age. The only thing older chickens can be used for really is bone broth. There is also a different diet for meat-birds.

When you go to slaughter the chickens, it’s best to do it quickly, for both you and the chicken. The usual way of doing this is by cutting off the head in one, quick chop with a sharp, heavy blade. When you go to pluck feathers, if you first dip the bird in hot water, the feathers will come right off.

When you go to pluck feathers, if you first dip the bird in hot water, the feathers will come right off. Once you’re done plucking, you will clean the chicken and cut it up. There are some good videos on the internet that show how. As I said, this is a quick summary on a big topic, and there’s a lot to learn if this is what you’re interested in.

As for breeding, some people have a designated coop and run just for breeding, which is probably nice if you are trying to get a specific breed. If you have a rooster in good health to mate, and some hens to go along, nature should take its course.

Now, one might expect the mother hens to lay on the eggs until they hatch. This isn’t always the case. Chickens have “broody” periods where they will stop laying eggs and lay on their fertilized egg until it hatches, however lot of breeds are bred to lay more eggs, and, therefore “bred-out” of being broody. So you will most likely need to incubate the eggs. You can tell if the egg is fertilized by a process I mentioned earlier called “candling”.

Closing and Miscellaneous Tips fo Raising Backyard Chickens

This article encompasses hours of research and a year’s worth of personal experience. I am capable of going into much greater detail, but that’s about a novel’s worth of information! So this is a summary basically so you know what you are getting yourself into, and if you do get chickens, I highly recommend doing your own further research. There are also some miscellaneous tips I have put together through my experience:

I would highly recommend a nipple-style watering system over the pan type. These are a lot cleaner and can be made from things like recycled buckets.

In the wintertime a heated waterer is a real luxury, otherwise, they will freeze a lot. These can also be homemade.

When designing things like the coop and brooder, it’s always good to build bigger than needed. This happens in everything, like the car you drive and the house you live in; it’s always going to be too small. My coop was designed for five chickens, so now I can’t buy anymore. If you plan to build a coop for five chickens, I would recommend building for ten.

There is a pecking order, where there are more dominant chickens in the pack. This may make introducing new chickens dangerous, as they may be pecked to death.

I raised chickens and had laying hens for 10 years while living on our farm in VA. It was a wonderful experience. We let ours free range most of the time, locking them in the run when the dogs let us know a predator was around. Fresh eggs were a bonus–we just loved watching the flock. I would also rcommend building your own coop. They are very pricey to buy new and ship to your location.