This article is inspired by the craftsmanship and elegance of early American homebuilding and traditional homestead construction. Further, it endeavors to be a worthy tribute to the late Dr. C. Keith Wilbur and his wonderful book Home Building and Woodworking in Colonial America. If there ever existed a way to pack a whole museum exhibit into a book, Dr. Wilbur found it.

~~~~~~~~

Trees and rocks. Unless there happen to be deer or other wildlife passing through, that’s what we see when we look out our windows. Just up the lane from us is a lovely but modest 18th-century house. From the road, the average passerby may not find anything especially noteworthy about it. It’s just a house, albeit an old one. The remarkable and almost incongruous thing, though, is that it is simply made from the native trees and rocks—essentially the same ones we see out our windows.

The word “simply” would seem to describe traditional homestead construction perfectly. At the same time, it is completely inadequate. There’s an intriguing mix of simplicity and sophistication, pragmatism and elegance—not to mention downright hard work—in these old structures.

That the early craftsmen could look out on a wild landscape and see their way to building a complete house from the materials at hand, with a collection of hand tools, is compelling. The craftsmanship was superb and it endures, still serving its basic purpose for the modern occupants generations later.

Raw Materials for Traditional Homestead Construction

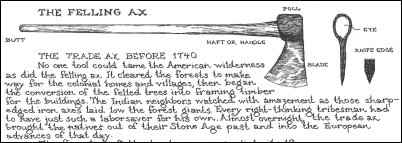

Putting the foundation aside for the moment—critically important though it is—the whole house-building project began with one simple tool: the felling ax. This object is familiar enough to us today, with its wooden haft—preferably hickory—and metal bit or head. But as with so many things that seem simple at first glance, there is a little more to it than that. It turns out that for an ax to cut efficiently, the bit’s profile is critical. Too much metallic meat on the shoulders, just behind the cutting edge, and the bit will stall prematurely in the cutting stroke. Not enough, and the edge can be too weak and not hold up well. A properly-sharpened ax in the hands of a skilled woodsman can be a surprisingly efficient cutting tool.

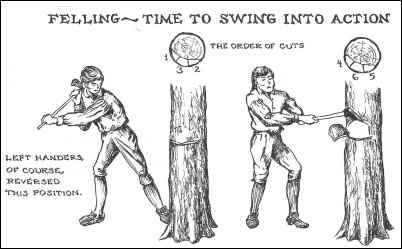

Of course, there are many subtleties to the techniques of felling trees with an ax, but we’re going to move right along onto the next stage of the project, where felled trees become logs, and logs become posts and beams.

Hewing

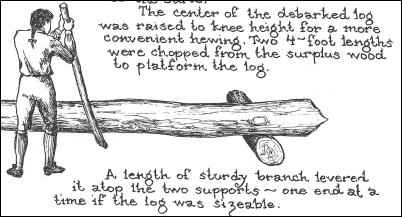

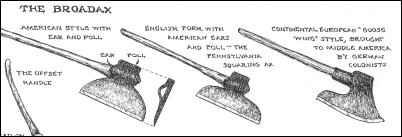

Today, a log becomes a squared-up piece of timber—a post or a beam—most often, in a modern sawmill. But early home builders could render superb posts and beams with only a few simple hand tools. Chief among these was the broadax.

The broadax, at first heft, is an awkward brute of a thing. Given its heavy, oversized, almost grotesque bit, and its relatively small, crooked handle, the uninformed axman might fairly bust a gut imagining how to fell a tree with such a ridiculous tool. But felling trees is far from the intent behind this tool’s ingenious design. The broadax has one purpose and one purpose only—making a flat, true edge along the side of a log, and it excels at this. As Dr. Wilbur pointed out, it’s really more of a chisel than an ax.

Even though the trees may be down and limbed, early home builders—housewrights—didn’t want to misplace the felling ax. For the broadax to do its work properly, there must be some prep work. The felling ax served to make chinks in the log all along its length. Then, when the broadaxman made his pass, the waste wood came off in chips rather than in long slabs that might otherwise run too deep or too shallow. These slice marks from the felling ax are still visible in many old, exposed posts and beams today.

Joinery

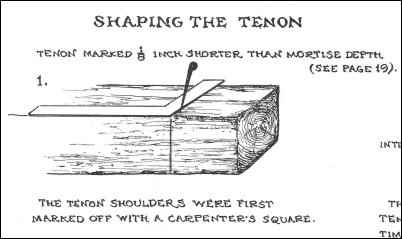

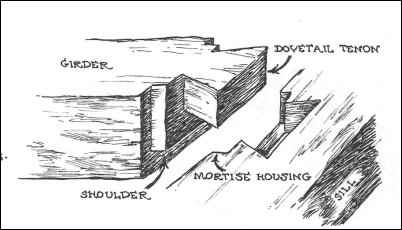

After the work and craftsmanship that went into hewing them, the big structural timbers would be worth more as firewood than anything else were it not for an ingenious method of connecting them together into a sturdy framework. That method is the mortise-and-tenon joint. The mortise is essentially a hollowed-out cavity in one timber, and the tenon is an end fashioned on another timber to fit into the mortise. The connection is a bit like a lock and key.

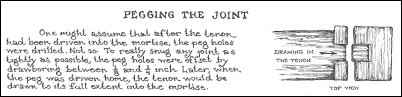

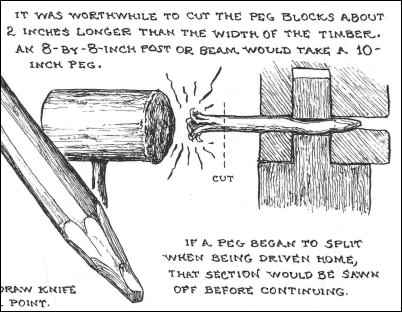

Of course, it doesn’t do much good to join two pieces of wood together without securing them somehow. So builders nailed the mortise-and-tenon joints, but not with any ordinary nails. They used treenails. Treenails are not metallic nails but are rather wooden pegs. The term “treenails” often gets changed to “trunnels.” Since the mortise was a cavity, and the tenon was a fashioned section of wood inserted into that cavity, drilling a hole through the two and driving a wooden peg—a trunnel—through would lock them together.

There was one more trick, though, to all the mortising, and tenoning, and trunneling. Rather than setting the joint, drilling straight through, and simply driving the trunnel in, the craftsmen would offset the holes through the mortise relative to the tenon. That way, driving the trunnel home would draw the joint in and lock it tight. Joiners used a metal pin—the drift wedge—to help line up the joint’s holes before finally driving the trunnel home.

So, ever so methodically, builders assembled the house frame through this process of joining posts, beams, braces, and other wooden members, all with the basic mortise-and-tenon joint, or variations on the theme. They used other familiar cabinet-making joints as well, like the dovetail, to lock floor joists into the sill members.

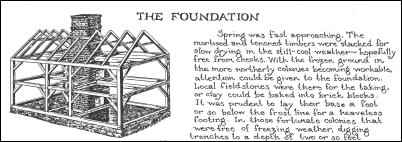

Foundation

Speaking of the sill, we’ve been leaving one not-so-minor detail out of the whole operation. The sill, of course, must rest on a sound footing, or all the fancy post-and-beam joinery in the world won’t count for much. The house had to have a foundation.

Since rack trucks full of foundation form panels and huge cement mixers to fill the forms once in place were things of the future, early builders used what, in many regions, was an abundant natural resource—stone.

Native stone was often plentiful, and it served as a sturdy foundation for a house. Depending on the region and soil type, it was important to get the building’s foundation down below the frost line, so that freezing and thawing cycles wouldn’t heave the structure up and down. In colder regions this depth would be several feet.

Not to slight the excavators—draft animals likely among them—and stonemasons who completed the arduous and skilled task of setting the foundation, we’re going to stay above ground for the time being and continue with the framework.

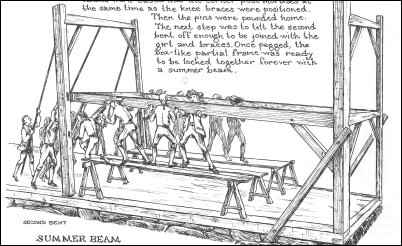

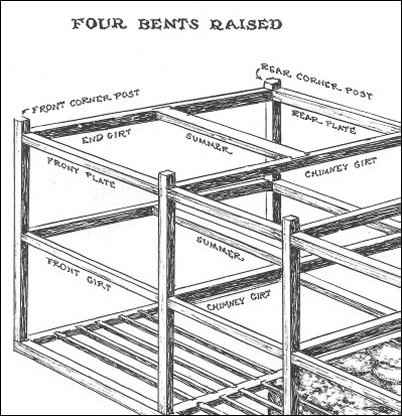

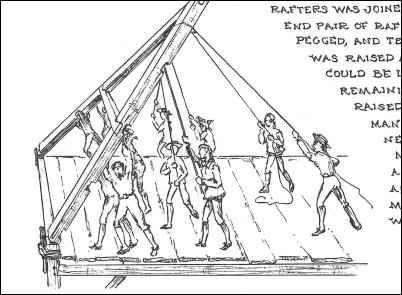

Raising

With temporary deck boards in place, builders could raise the main building frame in stages. Using those hewn timbers, craftsmen had built the framework for the outside walls of the building, employing the all-important mortise-and-tenon joints secured with trunnels. When ready, they lifted the framed walls—each a so-called bent—from their horizontal positions on the deck to their final, upright positions on the sill. There were even mortise-and-tenon joints where the bent set into the corners of the sill. Tying all the bents together yielded a large, cube-shaped frame.

Roof Framing

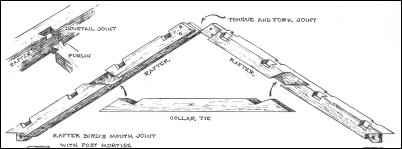

The roof framework had its own special set of timber joints, most more or less variations on the mortise-and-tenon and dovetail. There were two different approaches to roof framing. One had the rafters coming down to meet only at the support posts, with purlins running perpendicular between the rafters and dovetailed in. The other put the rafters on the top plate, whether between or on the posts, with support purlins under the rafters. In the first method, the roofing boards went on horizontally; in the second they ran vertically.

Sheathing, Siding, and Shingling

Now there’s a temporary floor deck with a timber skeleton rising above it. Still, it’s no more a weather-ready house than it would be a seaworthy ship if we were to flip it upside down and set it to sail. A house, after all, is a bit like an upside-down boat in which we walk around on the underside of the deck. The frame must have sheathing boards to form a hull—a roof and outside walls in this case. There were two basic ways that early craftsmen turned round logs into flat boards. Both involved sawing. One method was manual, the other more automated.

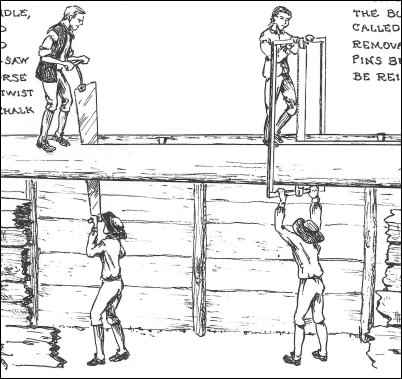

The manual method was with the pit saw, a contrivance that was pretty simple in principle but one that required considerable skill to operate. It also called for two operators, one above ground and one down in a pit. The pit was to give standing and walking room for the operator down below, and clearance for the saw to run up and down from above. A framework supported the log above.

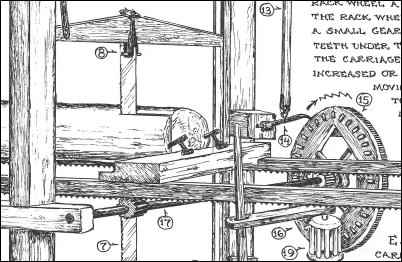

The water-powered sawmill was a bit like the Rube Goldberg version of the pit saw, except that it was far from being a joke or a caricature. It was labor-saving in that a fairly intricate mechanism replaced the two-man crew of the pit saw and took over the sawing operation. There was still a sort of pit, but rather than a live pitman being down there, an elaborate set of gears and such, powered by flowing water, did the work. Still, there was no shortage of physical labor required to run the sawmill. Workers had to load logs onto the saw’s carriage and tend to all manner of log positioning and mechanical adjustments and maintenance.

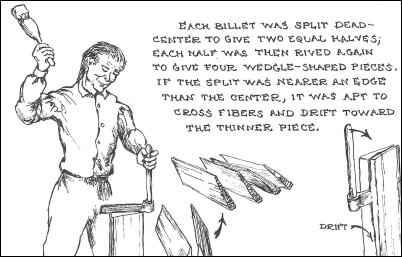

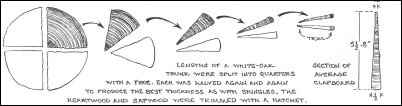

Of course the wall and roof sheathing, once on, had to have its final dress of siding and shingles, just as with any house today. The early craftsmen procured their shingles by riving them with a froe. This entailed splitting (riving) a short, upright log about the size of a chopping block into wide, slat-like pieces (the shingles). The tool of choice for this task is a blade mounted at a right angle into a wooden handle. This L-shaped tool is the froe. The shingle maker would hold the froe’s handle and strike the back of the blade with a club-like mallet or maul.

The rough shingles that came off the log often got their final taper and surfacing from the drawknife, a tool shaped somewhat like an old bicycle handlebar. The drawknife has two handles, like the handlebar, but between the them is a sharp blade. The operator draws the knife toward himself, using the blade to shave off any wood that is not desired as part of the final shingle.

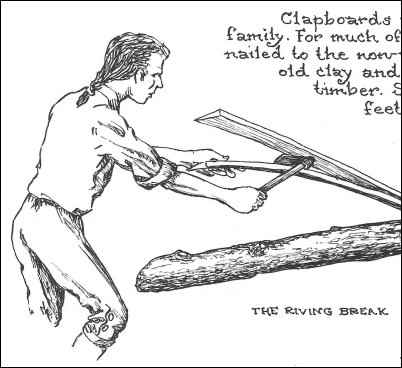

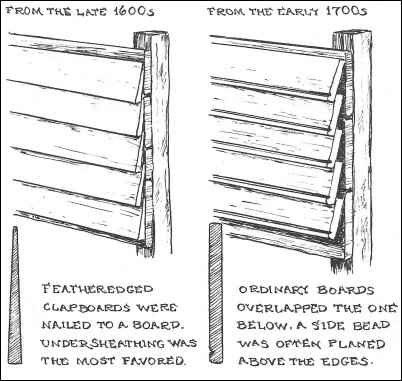

Early clapboard for siding also came about by splitting, or riving. The workman would set up small-diameter logs on an arrangement of other logs and branch sections that served to elevate and secure the workpiece. This was the so-called riving break. The worker would strike the froe, driving it into the log’s end, then continue to work it down lengthwise, eventually splitting out a section of clapboard. Certainly there was much more skill and nuance involved, but that was the jist of it.

Crafting the clapboards and shingles was one stage, and nailing them onto the house was, of course, another. But once in place, these “weatherboards” were the near-final stages in making the house the analog of being seaworthy for the landlubber.

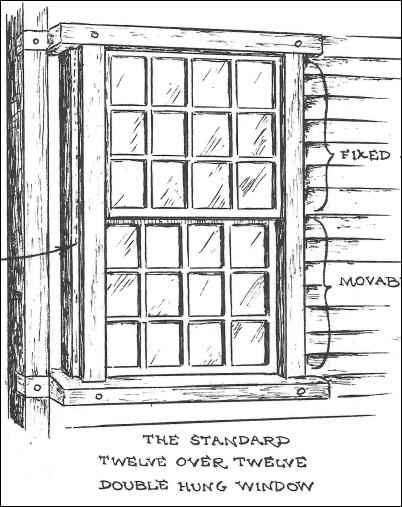

Doors and Windows

Although primarily structural and functional, doors and windows—like other components of the early American house—also often showed some style. The batten door, with its numerous variations, was a hallmark of early American architecture. It featured vertical boards on one side, and horizontal boards (battens) on the other. The door maker fastened the two sides by driving hand-wrought nails all the way through the perpendicular boards and out the other side, then clinching them over with a small turn on their ends. The nails came out, turned, and then the pointed end entered back into the wood. They appeared almost as staples on the side opposite the head.

Besides nails to hold them together, doors, of course, called for other hardware—namely, hinges and latches. The blacksmith supplied all manner of such items, including large strap hinges and thumb latches.

Flooring

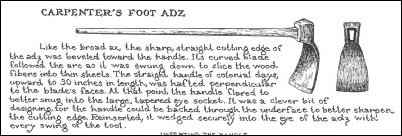

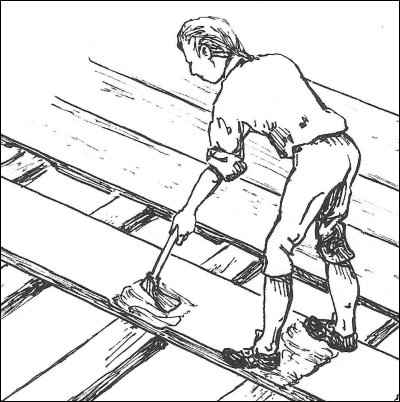

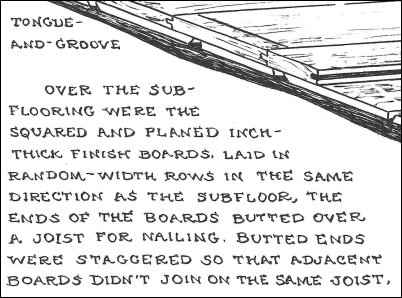

Using boards from either the pit saw or the water-powered sawmill, workers could now get the permanent flooring on the foundation framework. As with every stage in the project, flooring had its own nuances and it demanded different sets of skills. For one thing, since there might have been some variation in board thickness, workers often had to alter the undersides of floorboards where they met the joists to make them lay flat and true. For this job, another tool that may seem odd to us today was in order. It was the adz.

Just as we all know we shouldn’t run with scissors, it makes perfect sense that swinging a heavy, superbly sharp tool similar to an ax almost directly at the foot might not be a good idea. Though this is exactly what the adzman did, it was with enough care and skill that the risk was minimal.

Among other uses for the adz, at each section where a floorboard crossed a joist but rose too high above the general floor grade, the adz was the tool that took just enough off the bottom of the board to bring it down flush with the others. It was mainly the pit-sawn boards that called for adzing. With the advent of the water-powered sawmill, the saw yielded a more uniform cut along the board than even the most skilled pit saw crew could achieve.

Stairs and Finish Work

Stairs and interior finish work went through an evolution over the early American years. Stair building was an intricate craft unto itself. And door and window casings in old homes often reveal those early artisans’ skill with molding planes. There were hand planes for putting everything from a simple bead on the edge of a board to yielding very elaborate and fancy moldings.

So, after lots and lots of hard work—with no shortage of skill, craftsmanship, and ingenuity—the trees and rocks from the surrounding landscape became a house.

Of course, everything manufactured ultimately originates from raw materials of this good Earth. But with many things, especially many modern items, it can be a challenge to perceive any real earthiness about them. A post-and-beam house with a stone foundation is different. The framework is but a few steps removed from being a stand of trees. And the foundation stones are closer still to the earth. It’s little wonder, then, that many of us are so taken with the elegant yet pragmatic methods of traditional homestead construction, and the fruits of those skilled labors from yesteryear that still grace our landscapes, providing lasting shelter from the elements for modern occupants.

https://www.homestead.org/homesteading-construction/homesteading-with-pythagoras/

The blacksmith supplied all manner of such items, including large strap hinges and thumb latches. It is too soon for the cost of raw materials to affect manufacturers of construction equipment like mobile cranes. The worker would strike the froe, driving it into the log’s end, then continue to work it down lengthwise, eventually spitting out a section of clapboard.