I was born just before the end of World War II. As a child I often heard the term “victory garden” but by the time I was old enough to ask about it, I was told that the victory garden program was a thing of the past. It had been set up to help feed Americans at home, troops overseas, and suffering allies during World Wars I and II, a noble and notable chapter in the annals of our domestic war efforts. I have recently learned that the movement never died, that there are still some of the original gardens flourishing, and that the concepts implied in that earlier initiative have been co-opted by modern idealists, including homesteaders for whom the methodology is a natural fit.

Many years later I also learned that the noble purpose ascribed to the victory garden system had a dark and tainted side that may be unknown to those who want to reinvigorate the movement and carry it on.

The history of the WWII victory gardens is a hefty slice of American paradox—political, sociological, demographic. It links old discredited race hatreds to the finest of patriotic sentiments, with an over-arching ideal embedded in an endeavor we all admire: small-scale sustainable food production.

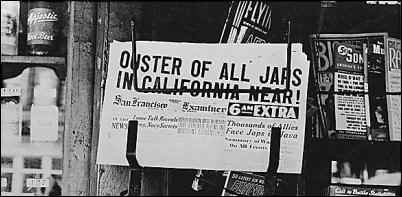

Though the gardens were first promoted in Europe and then the U.S. in the First World War, the story of the victory gardens really begins when Japanese bombs were dropped on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This act of war against the U.S., which was already committed to assisting in the war against the Germans in Europe, opened the floodgates of anti-Asian sentiment across the U.S. This was especially so in the Western states where the largest number of Japanese resided, some of them second- and even third-generation U.S. citizens. Their citizenship did not protect them any better than such formalities protected Jews in Europe. Billboards on U.S. highways warned, “Japs, Keep Going!” and the Japanese were often referred to as “Mongolians,” a term also applied to people with mental retardation.

Because Japanese families in America lived in their own enclaves and often chose to educate their children in their own language, they were suspected of spying for their motherland, though there has never been satisfactory proof of any Japanese American committing espionage. One military spokesman called them “inassimilable” and most officials demanded their isolation at least, and preferably, their deportation if not obliteration. It is an embarrassing fact that most Germans in America were not treated in the same way as Japanese simply because they were not so easily recognizable, thus adding the most blatant form of racism, that based purely on physical features, to this thorny chapter in our history.

In early 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 calling for the roundup and internment of the Japanese residing in the U.S., leaving great leeway to the states as to their manner of dealing with these purported national enemies. The entire west coast (and Hawaii) became an “exclusion zone” where people of Japanese descent could no longer reside. The states were unprepared and arrangements were hasty and flawed. Up to 1/16th Japanese heritage was enough to allow for internment. Japanese who owned properties and businesses were forced to make quick sales at a loss, if they were even that fortunate.

The results were catastrophic to the Asian communities, of course, but there was a spin-off that would widely affect all Americans. Many of the Japanese persons living in the U.S. were small-scale gardeners of considerable talent, who had been supplying their regions with up to 40% of its fresh produce. Truth be told, many white American farmers viewed the Japanese as a considerable threat—to their livelihood. They were glad to see the competition eliminated. Without consultation required or offered, many local communities seized Japanese farms and smallholdings. Taking away the gardeners and then urging other people to garden could be symbolized as the snake eating its tail.

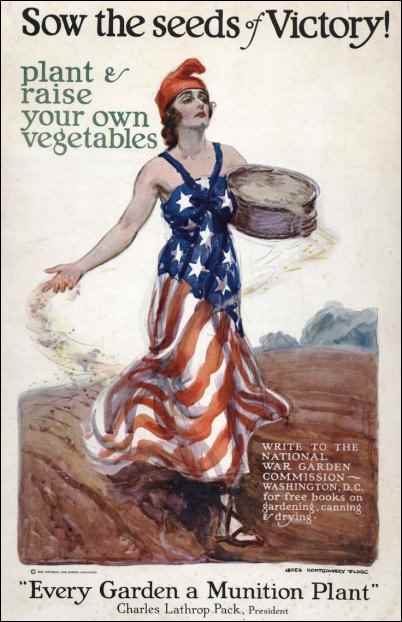

With full governmental sanction, including the imprimatur of Eleanor Roosevelt who initiated a victory garden at the White House, the victory garden movement was fully underway by 1943. It was put before the public eye with posters exhorting citizens to grow their veggies and fruits so that precious canned foods could be used to feed the troops and the starving allies in Europe. Slogans like “Plant more in ’44!” and “Sow the seeds of victory!” exhorted ordinary folks to “dig in.” Though the food industry expressed their discomfiture, it turned out that victory gardens were an augmentation, not a threat, to farmers. Some 20 million Americans participated in the Victory Garden effort, producing an estimated 40% of all the fresh food consumed in the country during the war years.

Whole communities responded with patriotic zeal. The schoolyard became fertile ground for victory veggies, and children were encouraged to hoe, weed, and water after school and in vacation times, thus making their own small contribution to the war effort. Urban areas donated unused swathes of land where locals could team up to till and harvest. Families could use their own private gardens as a source of income as well as a source of nutrition, supplementing what rations could not offer: fresh, wholesome foods. It was, it seemed, a win-win, and those who toiled in the gardens believed they were doing so for the big win.

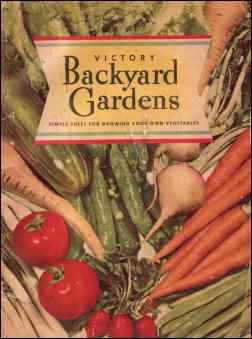

I found a marvelous book, all browned and crumbling, in my local thrift store: Victory Backyard Gardens, published in 1942, with an intro by the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard, who hated victory gardens before he liked them and famously spoke against Mrs. Roosevelt’s planned veggie plot before he recanted. In the book, which was widely circulated, Wickard emotionally declares, “Equipping one man for service in the modern fighting force requires the services of a score or more of civilians. One indispensable line of war production is food. The fighters need food, and the workers who equip the fighters need food to make possible the top performance which is demanded by the danger we are facing as a Nation.” The main gardening portion of the book was written by English horticulturist T. H. Everett who was to establish the New York Botanical Garden School, and Edgar J. Clissold, who later wrote about the seed industry.

With extremely simple illustrations (one feels a child could follow them), Everett explains “EVERYTHING you need to know” (to quote Johnny Carson) about backyard gardening in less than 100 pages. To his credit, Everett advocated and carefully illustrated that best of all small-scale intensive gardening techniques, double digging (see my article on Homestead.org, “Can You Double Dig It?“). He takes the amateur through the seasons of the year, planning and then planting the garden (50’x30’ was considered a small garden plot), crop succession, and earth hill or trench storage for potatoes and other keeper veggies. He covers tricky aspects of the gardener’s art like blanching and earthing up. Everett’s chapter on “the sick vegetable” could have been written by a doting mother: “lift up the leaves of your spinach and examine their undersides for aphids… notice every change in the appearance of your vegetables…if they are not doing well, find out why.” Clissold provides specific instructions for the cultivation of 60 vegetables, and someone named E. J. Werner contributed the section on fruits and berries.

The Department of Agriculture put in its own two cents in Victory Backyard Gardens, with numerous statistics such as how many veggies will be required by a family of four per week: potatoes, sweet potatoes, 11 pounds; tomatoes, citrus fruit, 8 pounds; leafy green, yellow vegetables, 12 pounds; mature beans and peas, ¾ pounds; other, 16 pounds. There are cartoon dos and don’ts and suggestions on where to apply for more help with starting and maintaining a garden: county agent, vocational agricultural teachers, Civilian Defense Council (oddly, Victory Gardens were considered a branch of what would now be termed “homeland security”). To locate the CDC, the advice is to “look for address in telephone book or call the Mayor.”

The victory garden concept spread quickly and doubtless offered a ray of hope and even pleasure to those stuck at home, worried about family members going overseas to wage war for them. Gardening is inspiring work, if tough at times, and gives back. If a family carefully followed Everett’s simple steps, they would have been rewarded with vegetables and fruits for the year-round. Household money could have been earned by the sale of produce, and above all was the satisfaction of contributing to the national effort to defend American freedoms.

The interned Japanese, meanwhile, suffered varying deprivations. Some lived in manure-filled stables in California. Some were sent onto lonely Native American reservations where the Indians received payments from the government for tending the aliens. Many families and their descendants chronicled their suffering and humiliation: crowded conditions, queuing for unpalatable food, little entertainment, few if any chances to go outside the camps. The budget for food for the internees could be as little as 45 cents per person per day. Japanese from warm climates like California could be sent to states like Wyoming with no clothing suitable to the cold winters.

Ironically, many Japanese were still keen to contribute to the war effort and grew their own victory gardens within the camps. Japanese young men, hoping to gain better conditions for their families within the camps, went to war for the U.S.; Japanese interns from the camps even volunteered for roles as “the enemy” in anti-war propaganda films. Only in one state were the interns offered decent conditions: though legally bound to isolate them, Governor Ralph Lawrence Carr did his utmost to treat Colorado’s Japanese population like human beings who had come to America for the right reasons and deserved to be trusted. The Indiana Quaker College, Earlham, invited a small number of Japanese-Americans to reside and study there. But such gestures were rare.

A few interned Japanese activists attempted to renounce their American citizenship as a form of protest and were of course considered traitors (this stance on the part of U.S. officialdom has since been retracted).

In general, the Japanese survived the camp experience largely by their cultural ability to endure hardship without complaint, a characteristic that was amply demonstrated after the 2011 tsunami and subsequent damage to nuclear plants.

When victory over the Germans came and later, over Japan, most Americans were pleased to give up gardening, but the slow recovery after so many years of military gear-up meant that those who kept their gardens were the real winners. In England and elsewhere, the gardens were still a vital necessity and their tradition has not ever fully died away.

Dowling Community Garden in Minnesota is one of the only two (large, well known) victory gardens that remain in the U.S. as actively tended and in production: “The Victory Garden program got a small start nationwide in 1942 and by 1943 it had become a huge phenomenon. In 1943 the Twin Cities alone had 130,000 gardeners (20 million nationwide) and by 1944 it was estimated that 40% of all fresh vegetables in Minnesota were grown in Victory Gardens.” Dowling gardens still raise veggies, while another still extant community garden, Back Bay Fens in Boston, mainly features flowers.

What happened to the Japanese, many of them gardeners as fully able as any American to produce healthy vegetables and fruits, but who were transplanted to the depressing, desolate and dangerous life of the concentration camps? After the war, as the victory gardeners, who were indeed victorious, downed spades and looked to a more prosperous future, the Japanese were released from their internment with $25 each for train fare. Most had lost everything in the three-year interim; only a handful had been lucky enough to have an American neighbor who tended their property in their absence. Most were entirely destitute as a result of the internment.

President Jimmy Carter called for an investigation of the WWII internment of Japanese and others and a select commission determined that the system of relocation and isolation had been absolutely uncalled for. President Reagan followed Carter’s work by awarding the commission’s recommended sum of $20,000 to each internee as reparation (that would be about $50,000 in today’s dollars). Presidents Ford and George H. W. Bush continued to extend reparations.

According to Wikipedia, “since the turn of the 20th to 21st century, there has existed a growing interest in victory gardens. A grassroots campaign promoting such gardens has recently sprung up in the form of new victory gardens in public spaces, victory garden websites and blogs, as well as petitions to both renew a national campaign for the victory garden and to encourage the re-establishment of a victory garden on the White House lawn. In March 2009, First Lady Michelle Obama, planted a 1,100-square-foot “Kitchen Garden” on the White House lawn, the first since Eleanor Roosevelt’s, to raise awareness about healthy food.”

Beyond this national nod to the idea of gardening as a healthy food intervention, the victory garden name, if not the movement, has caught on among homesteaders. There is more than one blog proclaiming kinship with the victory garden ethos: www.Modernvictorygarden.com, proudly declares, “Harkening to the self-sufficiency of previous generations who planted victory gardens in their front and back yards as a means to support their nation’s war efforts – today many are undertaking the challenge of declaring independence from corporate food systems, reducing reliance on fossil fuels to bring food to the table, and cultivating a more healthy and fulfilling life. This grass roots revolution is occurring in today’s modern version of the victory garden. The “war” is a revolution—and the battleground is right here on the home front. It is all about taking back responsibility and control of our own food supply.”

In California, the Victory Garden Foundation is aggressively attempting to revive the principles of the original movement. With step-by-step advice on how to bring neighborhoods into the project, and six regional groups already committed, this looks like a genuine offshoot of the old rootstock. The VGF had placed these statements on its website:

Mission:

Our mission is to support the growth of food at home by neighbors connecting and sharing with each other through the organized growth and harvest of Victory Gardens in communities.

Our mission is carried out through education, technical assistance, mentoring, and encouragement through the Internet, workshops, and hands-on participation.

Vision:

Inspire individuals to build their community by building sustainable food systems, at home, that are equitable, ecologically sound and that connect neighbors in a positive and productive way.

Far from California with its “fruity, nutty” element, the rather more stolid citizens of Arkansas are also involved in victory garden, or community garden efforts, in response to the current and seemingly endless national recession. In February, 2009, in the early days of the crisis, The Economist reminded readers of the Victory Garden program of old, and reported from Little Rock: “Although Arkansas is an agricultural state, urban gardening has not always been popular. But now victory gardens are springing up in backyards, school grounds and even on front lawns in posh neighborhoods. Many gardeners are focusing on ‘heirloom’ plants—rare varieties from earlier times that do not appeal to agribusiness.

“Classes are being offered on canning vegetables and raising chickens. The Station, a new grocery store about to open in Little Rock, will sell primarily local foods. Heifer International, a non-profit group that hopes to fight world hunger and poverty through self-reliance and sustainability, will host a conference in the city later this year to encourage the use of local produce in school cafeterias.

“The two-acre Dunbar Community Garden in Little Rock has served as a model for several years. More than 600 students a month have learned about gardening there. The students can take these lessons home and recreate them in their own back yards. The garden, attached to an elementary and middle school, allows inner-city students to taste fresh-grown fruit and vegetables, sometimes for the first time in their lives. Produce grown in the summer months is sold to local restaurants.”

And if further proof is needed, I have seen an extensive garden in the backyard of my grandchildren’s elementary school in Carrboro, North Carolina.

It is less important what the specific connection is between these initiatives and the original wartime Victory Garden movement, than to keep its best motivations in mind. One suspects that those already gardening want those who are not to join in the fun and stretch the green, veggie green, where the green, money green, is not doing the job. Any way you look at it, there’s still a victory to be gained.

Some of the Japanese internment camps have been slated for preservation as national sites of remembrance, “reminders that this nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency.” Innocent citizens caught up in a war overseas and repercussions at home, the Japanese Americans have been commendably quiet about what they suffered in those years. Perhaps the victory gardeners of today can dedicate their efforts to them.