Whether it be the kitchen, workshop, in automobile emergency-kits, or simply junk drawers around the house, shop, or barn, having a cutting blade close at hand is a must for rural life.

A few years ago, I penned a story about how to sharpen knives. Getting and maintaining a good edge on a blade is an art form. Even though I grew up in the country, my dad had no clue of what it took to get a knife really sharp. His idea of sharpening a dull blade was a trip to the bench grinder. While that would give him a temporary edge sharp enough to hack through baling twine or wiring on a tractor or truck, the heat from the fast-spinning grinding wheel took the temper out of the blade so any edge was short lived.

Many years later I had an impromptu run-in with an old timer who carried a small sharpening stone in his pocket and could work magic with it. I set about trying to learn how to make a knife blade sharp enough to shave and hold an edge.

Over the next several years I learned that all cutting blades, like men, are not created equal. Some have the natural potential to be sharper than others. Before we get too technical, let’s first discuss the different kind of knives you might want to surround yourself with.

Types of Knives

To make this real simple let’s break it down to two categories: kitchen knives and everything else.

I’ll start with “everything else” since that’ll take care of us where we live most of our life: out and about away from the kitchen. These knives include what you might carry in your car or truck, in a toolbox, in the garage or barn, and, more importantly, in your pocket or on your side.

By the time you’ve spent any amount of time at all living in the country you’ll undoubtedly have discovered the benefit of carrying a pocketknife. I’ve carried one since I was about eleven years old. My wife carries one in her purse, and our college-aged daughter keeps one in her car and another one in her hiking backpack. Our son, who has traveled the world doing mission work and spent much of the last several years living in different, unfamiliar environments, carries a folding knife in one pocket and a small sheath knife with a paracord-wrapped handle in another pocket. While you’ll likely never find yourself depending on a knife to save your life, it still pays to have one within reach.

Types of Pocketknives

In mainstream America, you rarely hear people talk these days about types of knives, but in more rural areas you’ll still occasionally hear people refer to folding knives by type; they have names such as pen knife, trapper, stockman, jackknife, or, an old favorite, Barlow. All pertain to folding pocketknives but that’s where the similarities end.

First, the term “jackknife” refers to any folding pocketknife. It can have one, two, or three blades hinged on one or more ends of the handles.

A small, thin, folding knife is usually called a “pen knife” (think something small that a businessman might carry). These might have one or two blades, long and slender. If you think the knife got its name because it resembles a writing pen, well, you’re close. The name was given to the small knife kept to sharpen quills for writing in the quill-and-inkwell days, long before the modern ballpoint pens. Originally the penknife had a fixed blade, but over time small folding knives were created and the convenience of carrying dictated that the new options would be used as “pen knives”.

A “trapper” commonly refers to a two-blade, mid-sized-to-large folder with both blades hinged on the same end of the handles. One blade will come to a fine point with a slightly curved back edge near the end, otherwise known as a “clip” blade, while the other will be angled and blunt on the end, called a “spey” blade. Of course, these knives became standard tools for fur trappers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and are still popular today.

A “stockman” is, in my opinion, the ultimate pocketknife. They come in small, medium, or large sizes. A main feature of a stockman is the three blades with two hinged on one end and the other hinged at the other end of the handles. The blades include a clip, a spey, and a sheepsfoot. A sheepsfoot blade will be a straight line on the cutting edge, but curved on the end from the back edge down to the end of the cutting surface.

A “Barlow” knife refers a one- or two-blade knife with a tear-shaped handle with a sizable metal bolster on the small end where the blades are hinged. While I own a couple Barlow knives, I tend to not carry them because of the ample size.

My first knife was a Barlow my dad gave me when I was about eight years old. While writing this article I did some quick research and discovered that Barlow knives were first made in England in the 1600s. According to the online “History of Barlow Knives” our nation’s first president, George Washington, carried a Barlow pocketknife. And one of my fellow Show-Me-State writers, Samuel Clemons, a.k.a. Mark Twain, referenced a “real Barlow” in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (and Huckleberry Finn) printed in 1876.

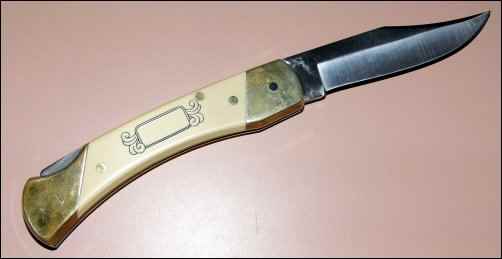

In the last half of the 20th century, the single-bladed “lockblade” knife design became popular. At first, the thumb-operated lock release was integrated into the back edge of the handle. More modern versions often have lighter skeletal-style metal handles with the locking mechanism as a spring-loaded flap of metal which holds the blade locked open until you push it out of the way to swing the blade closed.

The final type of folding “pocket” knife I’ll address is the multi-bladed tools that started as military-issued equipment and eventually evolved into the modern “multi-tool” which became popular in the 1980s. I had a U.S. Marine surplus pocketknife as a teen. Ironically, I saw one at a local flea-market recently and would have bought it if it hadn’t had such a hard life.

The high-end version—solely due to craftsmanship and a superior marketing plan—is the Swiss Army knife: the signature red-handled everything-but-the-kitchen-sink tool, complete with a pair of tweezers, a needle, and a toothpick. Then, in 1983, the Leatherman company was formed and took the tool-based knife to an entirely new level with a pair of pliers integrated into their model. The main downside to these utilitarian Jeeps of the folding-knife world is that they’re generally too large to be useful as a “pocketknife”. But if you have big pockets, or can wear a belt case, there’s no doubt that a multi-tool can be a homesteader’s best little helper.

Types of Fixed Blade Knives

If you thought there were a lot of folding knives to choose from, the fixed-blade knife market is just as varied. While some have specific purposes or are better suited for different jobs, in most cases it comes down to simple preference; whatever feels best in your hands.

There are a dozen or more fixed-blade designs that can be found on the market. But since I’m a user, not a connoisseur, of blades, for this discussion we’ll just stick with the basics. These are knives I, or others I know, own and use in real, everyday life. Most of these knives come in a wide array of lengths and thicknesses—and again personal preference will ultimately dictate which one you choose—so we’ll focus on blade shape more than overall size.

The “clip point” is, in my opinion, a great knife for processing animals. We raise chickens, meat rabbits, and hogs, and I also hunt and fish often to put meat on the table. With exception of an occasional hog or deer, I process all the meat we eat or store for later use.

For years, I used a clip-point Old Timer with a 4-inch blade. It was a solid old knife and served me for many years. When our son began hunting as a young boy I passed on that knife to him to use, which he still carries when afield today. For the next several years I used a custom-made clip-point knife made by a friend and knifemaker. Just recently, I decided to retire that knife and buy another small Old Timer for processing wild game and homestead meat.

Benefits of a clip-point blade are that it can be used for slicing in the traditional sense, but the narrow, slightly-hooked tip also makes it ideal for skinning and removing entrails. The back edge of the blade is not sharpened so it works well to lift hide out of the way, while the fine tip is ideal for precision work around orifices, scent glands, and other areas to be avoided or approached gently.

Additionally, many thin-bladed fillet knives for cleaning fish carry a clip-point shape.

The next several knives to be discussed will follow a progression of how the tip of the blade is shaped. You’ll see from the accompanying photos what I mean, as each blade mentioned will get more curved toward the point.

First is the “trailing-point” blade which, instead of following a straight line from the tip of the handle to the tip of the blade, has an ever-so-slight bow backward at the point. I’m not sure of the original purpose of the shape of the tip, but can attest that it feels good in use. Perhaps the most famous trailing-point knife is the fighting knife created for, and carried by, Jim Bowie. The signature of a trailing-point blade is that both edges of the top are sharpened.

Another variation on the trailing point is the “modified trailing-point” which has a slightly thicker area of blade near the point. This style has become very popular in recent decades for being a good skinning blade.

A “straight-back” blade is simply what the name implies. The back edge of the blade follows a straight line from the tang of the handle through to the tip of the blade. This shape is often found in homemade knives, especially those made from old files or saw blades. But they are also available commercially, and make good, solid, everyday knives to have in toolboxes, glove compartments, and as backups in backpacks or bug-out bags (for those preppers among us).

The next progression in tip shape is the ever-popular “drop point”. They get their name, again, quite literally because if you were to hold the handle between thumb and finger with the tip pointed down and release your hold the knife will land squarely on the point.

The spine of the blade runs straight from the handle toward the tip until the last small portion where it will curve downward toward the point. The spine will not be sharpened, which makes it another good choice for skinning duties during butchering.

Drop-point blades are very user-friendly and utilitarian, which is why you’ll find the shape in many survival knives. Not having the point flush or proud of the back edge of the blade makes it less likely to nick things you might not wish to cut. The design also makes for a very strong, rigid blade all the way to the tip.

The next progression is a “spear point” design. The edges of the knife, both spine and cutting, will have essentially the same shape. In some cases only the cutting edge will be sharpened, but more often than not both edges will be honed for cutting.

The signature of a spear-point knife is a symmetrical blade where both sides are nearly equal and meet at the point, which is at the tip of an imaginary line which runs through the blade like an equator. The place you’ll most often see the spear-point design is in throwing knives.

The final shape we’ll talk about is the “straight edge”. Not to be confused with the blunt-ended shape of a straight razor, a straight-edge knife-blade will have a straight line for the cutting edge from tail to tip. However, the back edge of the blade will curve significantly near the tip to meet the sharpened edge.

The Best Kitchen Knife

While you will find this blade design as one of the options in some folding pocketknives, perhaps the most recognizable example can be found in your kitchen butcher-block knife set. The design is often called a “Santoku” knife, a Japanese name which means “three virtues” or “three uses,” a blade which will slice, dice, and mince equally well. Of all the options in our butcher-block set at home, the Santoku is my favorite when my wife calls on me to chop vegetables for stews, soups, or stir-fry dishes.

One last aspect to consider is the cutting edge. Options include:

“Double bevel” where each side is ground at an angle toward the fine cutting edge, also sometimes referred to as a sabre grind.

“Single bevel” where only one side is angle ground and the other remains perfectly flat. This is also called a chisel point.

“Serrated” where the blade has notches or other indentions in a row to create more of a saw-tooth cutting edge (which is common in kitchen bread knives, and some survival or hunting knives)

“Hollow ground” where both sides of the cutting edge have a concave grind ending at a fine pointed edge.

“Convex” grind is the most basic where both sides of the cutting edge are gently sloped, or rounded, toward the cutting edge with no definite angle to the grind.

And “double bevel” or “compound bevel” is one of the most common. In this instance, there will be a wide-angled grind leading toward the cutting edge, with a second more proud angle on the very last bit of metal where the two sides of the blade meet up.

You can learn more about the different angles and benefits of them elsewhere on Homestead.org, which I’ll reference and give the link to in just a moment.

A Few Last Words

If you’ve already made that transition to the country, or you grew up there, then you’re well aware of the need for having good cutting blades around you. I always carry a folding pocketknife, usually with two blades, minimum. Just like how my wife likes to change the purse she carries from time to time, I sometimes mix it up and carry a different pocketknife. But the two constants are that I’ll always have one of some sort in my pocket and it’ll always be sharp.

To learn more about how to get a knife sharp and keep it that way check out my story titled “Razor’s Edge Extreme Knife Sharpening” at Homestead.org.

In my pickup truck, you will find a neck knife (small knife on a lanyard) with a modified spear-point blade. I grab the knife off the rearview mirror where it hangs when I head out to hunt or do farm work on my remote property. It’s great for slicing open bags of animal feed, cutting baling twine, or having as a quick blade to grab in case of an emergency.

Above the visor you’d find a drop-point Buck 4-inch hunting knife with a thin manufactured plastic handle and plastic or Kydex-style sheath. Like the others, this one is razor sharp. It’s primarily my backup in case I forget me Old Timer hunting knife at home.

I’m not what you would consider a “doomsday prepper”, but I do like being prepared. So I carry a nylon bag in my truck which holds a rain poncho, some first-aid supplies, a folding shovel, a hatchet, duct tape, a small cooking-grate, matches and other firestarters (lighter, flint and steel, fire starter cubes), a 6-inch lightweight camp skillet, a small bottle of cooking oil, some other items… and another small folding-knife. I have yet another small fixed-blade knife in my tool pouch in the truck. With a propensity to drive older pickups and tractors, you always want to have a tool kit handy, and no set of tools is complete without some kind of utility knife.

Aside from my box of sharpening stones, steels, strops, and accessories in my workshop, I also keep a small, diamond sharpening-stone in the console and a ceramic sharpener in the door pocket of my truck. I have a small, natural, Arkansas sharpening stone in my hunting backpack, and another small blade and hook sharpener in my trout-fishing vest with my fillet knife.

Like I said at the beginning, I’m not a blade expert or even an enthusiast for that matter. I don’t walk around with a big sheath knife on my side while in town, and I don’t have a bunch of swords or medieval blades displayed or sitting around in my house. What I am is just a guy who grew up in the country, who still likes living in a rural setting, who spends most of his free time on the water, in the woods, or afield either, working or relaxing. And there’s hardly a day goes by that I don’t find a need for a cutting tool. And I suspect the same holds true for you, too. I hope something I said helps you pick the most helpful knives for the jobs you face on the homestead.

Comments