“Come along, come along, make no delay,

Come from every nation, come from every way,

Our lands they are broad enough, have no alarm

For Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm.”

– Song lyrics from the time of the first Homestead Act.

Long before the rumble of civil war deafened our nation, there was a rattle and clatter heard from a distance, the clamor for more smallholdings for the free farmer, and the cry for potential plantation spreads for slave owners.

It was the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, which championed homesteading west of the Mississippi, citing the iconic significance of the “yeoman farmer” and the efficacy of family farming units as distinct from plantations. Vegetarian utopian socialist liberal Republican Horace Greeley advised, “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.”

The not-so-well-hidden agenda of the Greeley and his ilk was to block any further states from being designated as slave holding, a contentious issue that plagued the country for years before the outbreak of hostilities between North and South. As settlement crept ever west, the government’s final solution to the thorny subject of slavery was the Kansas-Nebraska Act that threw the responsibility of decision-making back onto the states. In Kansas a mini-civil-war was waged on this issue in the 1850s; there, a firebrand with the humble name of John Brown cut his teeth fighting for the abolitionist cause.

The Homestead Act of 1862 opened up western territories to expansion in 160-acre plots known as quarters. In order to get a plot, one had only to:

be a free citizen or intended citizen;

be 18 years old or older;

never have waged war against the United States (a clause both sensible on its face and also obviously intended to keep Southerners out of the game);

pay $18.00 in fees;

promise to improve the land with buildings, wells, and crops over a five year period.

That being accomplished and duly witnessed, the settler would own the property outright.

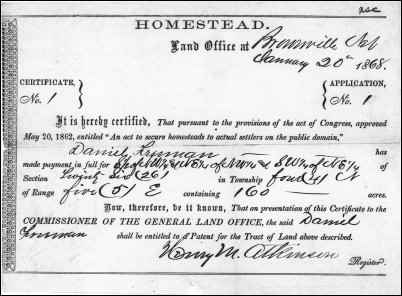

The first homesteader on record after the passage of the Act was the well-named Daniel Freeman, a Union army scout and physician who inveigled his local Land Office to open up at just after midnight so he could stake his claim. A quintessentially American man, Freeman improved and gained his claim, married a mail order bride, and once took a case to the superior court successfully opposing the teaching of Bible stories in school. It is on his homestead in Nebraska (at the time just a territory) that the National Homestead Monument stands, a tribute to Daniel and other free men and women who took a chance and won a great prize – a plot of good American soil.

Simple and desirable as the outcome seems, only about 40% of homesteads occupied were actually claimed by the above process. Most were abandoned because the lands offered were unrelentingly inhospitable. The secret was that apart from portions of California and Oregon, most of the West was dry and dusty or mountainous and rocky. The best land, that which lay in alluvial plains with copious water and temperate climatic conditions (i.e. most of the East Coast) was already occupied, in some places already crowded, by 1862. The Act wasn’t exactly a flim-flam but it wasn’t as good a deal as it seemed. A man or woman’s courage could flag, or determination fail, after two or three years of living in dirt houses, finding dried up water holes, trying to quell hunger with spindly harvests, and watching family members die by snake bite, snowdrift, thirst, and childbirth.

It was the vast area known as The Great Plains, or simply “the prairie,” that was opened up to settlement in 1862. Lying between the Mississippi and the Rockies, it was windy, thirsty, cold and baking land of maddeningly constant winds, singing grass or no grass at all, home to snakes, mournfully howling scavenger coyotes, Gila monsters and some very angry Native Americans, many of whom had been forced there by earlier “voluntary” resettlement initiatives like the legendary and disgraceful Trail of Tears. These tenacious tribes were not about to be pushed off their territory again, and they no longer had the slightest patience for whites.

Still the Act attracted newly arrived immigrants in droves (100,000 came to North Dakota in a twenty year period), along with those carrying other agendas than the mere thirst for raw land. Polygamous Mormons headed west as they were hounded out of the conservative East. Europeans including Ukrainians, Swedes, Germans, Dutch – organized, highly motivated groups hungry for religious and economic freedom – came to stay, building churches and schools almost as soon as they built houses. Freed slaves followed after the terrible war was over, willing to try new life anywhere except the still-hostile Deep South. The Homestead Act went into effect on January 1, 1863, the same day that Abraham Lincoln (see Part 2) issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Coincidence? I don’t think so. Women could also claim, and many did. In fact, the hordes of settlers came so fast and thick that in Nebraska Territory in 1871 a “herding” law was passed making stock owners responsible for any damage their animals did to the crops of their neighbors. This obviated the immediate need for expensive fencing and made life on the open range less risky.

Not long after the Act was passed, a coast-to-coast railroad was completed, a lucky break for those near the line and an indirect boon to everyone living west of the Mississippi. It sped up the western migration and, with a complex line of stage coaches, hauled adventurers like the young Mark Twain from the staid East to prospect and comment, to the benefit of us all. Settlement no longer depended on oxen and wagons. Towns grew along the rail and stage lines.

People were not the only movers west. Plants like tumbleweed and European grasses and grains hopped on board either by design or by accident. It has been said that nearly all grass species on the Great Plains today were imported in the western migration.

Just as the settlement of the forests and river lands is associated in our minds with the humble log cabin (see Parts One and Two) the settlement of the Great Plains is typified by the sod house. The sod house seems to have come in two types: horrible and worse. Horrible because a house made of dirt is filled with all the things that dirt is filled with: creepy-crawlies, plant tendrils, constantly falling dust particles and, well, filth. Worse because of the only available heating fuel: buffalo chips that gave off a fine dust that stuck to every surface.

“The hinges are of leather and the windows have no glass While the board roof lets the howling blizzard in; And I hear the hungry ki-yote as he slinks up in the grass’Round my little old sod shanty on my claim.”

Cut out of the ground in chunks four-inches thick by a plow made for the purpose (called a breaker or a grasshopper), sods were stacked to overlap (grass side down) like bricks, and were left in long slabs for roofing when no wood was available. The houses were dark inside, but the bright side, as it were, was that sods provided near-perfect insulation, keeping heat outside in the summer and inside the winter. It was possible to white wash the interior and to plaster the outside walls, considerably diminishing the sense that one was living in a dirt palace. Those who could afford it laid down strips of carpet or procured, at great price, puncheons, or flattened logs, for the floors.

There are many mid-20th century accounts of the life of the “soddies” recorded by old people who grew up in sod houses. These can be found on cyberspace or in regional museums in the Great Plains states, and are well worth reading/hearing. One such recollection, of a sod schoolhouse, comes from NebraskaStudies.org: “The floor was of dirt and during the cold winter of 1884 the teacher’s feet were frosted. Later a quantity of straw was put on the floor which made it warmer but proved to be a breeding place for fleas. This was not conductive to quiet study but did afford the children some bodily activity.” (Isabel Fodge Cornish, in Pioneer Stories of Custer County, Nebraska, collected by Emerson R. Purcell.)

There are only a few sod houses still extant, since they would of course deteriorate over time, leaving at best some mummified ruins. They were meant to last about the length of the claim period – five years. Some, owned by more affluent families, were built to two stories, and with white washed walls, deep window insets and polished wooden floors, had an unexpectedly elegant look. In fact, many people loved their sod dwellings. The materials were free — nature’s bounty just waiting to be collected. The insulation was a great advantage in a desert climate where temperatures could range from over 100 in the summer to well below zero in the cold months. And it was ownership, for most of the settlers, a first. Whether they came from the crowded cities or played out rural areas of Europe or from the increasingly polluted East Coast, they were grateful to have a place of their own. They learned the arts of homesteading as they lived there, and most reporters speak of the kindness of neighbors, forging a stronger bond than ever in the cities because of common deprivation.

By 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner was able to deliver a learned if not entirely accurate paper at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago entitled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” The West was so over!

By the early twentieth century, nearly all land that could be practicably managed in small holdings was occupied, despite the drop-out rates from abandonment and death-by-farming. Later homestead acts would offer larger plots of land, with the expectation that occupants would use it primarily for grazing, fencing and caring for it minus the need to subsist entirely within its boundaries.

One spin-off of the Homestead Act was employment for the military which was charged with making sure that the new settlers were safe from Indians. Forts were built all through the new territories and it seemed, if you built a fort, the braves were sure to come. It was the beginning of all-out war on America’s natives, waged by America’s latter claimants, and it could have only one outcome, certain from the start.

Another result of living in a sod house on the prairie was the first recognition that living on your own land had a downside: it could be terribly lonely. While Easterners may have felt marooned in their cabins in the dark forests, they had at least bird-song and squirrel chase for entertainment. On the prairie there was nothing, nothing, nothing. Any critter that might happen by was almost surely poisonous or vicious, the land was as flat as the word “plains” implies, and there was an pervasive low howling wind. Women were particularly affected by this alone-ness, since it was men who rode out to check on the stock and buy supplies, being gone for days at a time.

Two other spin-offs of the Homestead Act were selfishness and fraud. Selfishness could take as benign a guise as children of homesteaders rushing to claim adjacent land as soon as they came of age. Families often banded together to stake claims along a river or simply to share labors and have neighbors with people of like mind. But survival makes graspers of most of us and disputes about water and the aforementioned herding problems were rife as settlers struggled with the elements and each other. These giant consolidated farms without hedgerows became the basis for, and perhaps the cause of, the Dust Bowl, a tragic legacy for the next century.

Fraud was another matter. Often the subject of cowboy movies, water theft was a crime perpetrated by small, stealthy degrees. There are, it is said, two great laws regarding water rights: (1) water flows downhill towards the lowest point; and (2) water flows uphill towards money. Under the guise of individual ownership, crooked cartels lodged dummy claims to land along rivers, and once the prize was gained, the water was available to all – for a price. Subsisting in the earthly equivalent of Hell, homesteaders could not live long without “cool, clear water.” The men who plotted this acquisition of nature’s vital liquid became known, in cowboy movie parlance, as “crooked, low-down, yellow-bellied, side-windin’ varmints.” But the entrepreneurial evil geniuses could justify their perfidy by pointing out that the Homestead Act allowed such practices, in its letter if not in its spirit.

Another spin-off of the Act and the actors in the drama of homesteading was the heroic portrait that was being carved out, shot out, saddle-wearied and rode hell-for-leather in the dying days of frontier settlement: the taller-than-life, tougher-than-nails, handsomer-than-your-husband American cowboy. By implication, his opposite number also came on the scene as a part of our mythology: the Indian brave.

However, the most pervasive influence on our character was forged by the picture we all share of hardy souls trekking in wagons, facing hostile natives and inhospitable nature, living day by day with faith in the future despite every sort of horror and deprivation. They were the nation builders who settled the Great Plains, and they are us.