I walked off the plane in March expecting to get smacked in the face with heat and dust. “115 degrees,” they told me, “and the dust will cake on you, are you sure you want to do this?” Instead, it was 85 and drizzling when Joseph, one of my host organization’s drivers, picked me up at the airport. “A blessing,” he told me, and indeed it was—as soon as I got off the plane, I knew that despite the city’s bare appearances, things could grow.

Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, is very likely like nothing you’ve ever seen before. It was certainly new to me—despite working on HIV/AIDS issues for several years and a having Master’s degree that focused on international development, I’d never set foot in Africa before. As you might imagine, no amount of dire warnings could have kept me from taking the opportunity to teach advocacy strategies to a group of HIV-positive men and women in Juba. Adding icing to the cake, my host organization focused almost exclusively on development through agricultural growth—as a homestead admirer, I couldn’t wait to get out and see what was being done, despite my current city-girl status. There was certainly a lot to see: the Nile, the treeless city surrounded by green hills, the marketplace of imported goods (including winter coats and fur-lined boots!), the United Nation’s planes, vans and buildings, the university, and the hospital. But mostly I had questions about what Juba could do to improve the quality of life for its residents quickly and, to my mind, one of the top answers is encouraging the development of homesteads.

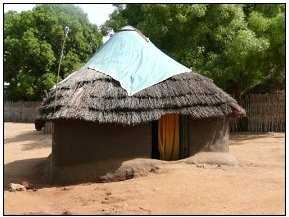

Hot and dusty half the year, most work that gets done in Juba is done during the rainy season, March to October. Work continues until almost all roads are completely impassable. With just two paved roads, the second built during my visit, the majority of the infrastructure in South Sudan is washed away in the rains and not fixed. Running water is scarce. Most potable water comes from trucks that go from well to well, dropping of water that is potable only for those who have never left. Electricity, when available, comes from generators in the middle of compounds.

Any native Sudanese who want to can pick a plot of unused land and claim it for themselves, and unused land is not scarce. Instead, much of the “city” is empty patches of land, barely needing clearing, covered with piles of half-burnt garbage picked over by goats, hens, and several other animals that would look tasty were it not for their diet.

Personal safety, despite a strong international presence and dramatic improvements in the past few years, is still a problem. I was stunned one morning to hear from one of the women in my class that there had been a shooting at the market that morning, and even more surprised at how dismissive she and all of her classmates were at my concern. This, they told me, happens all the time—some Dinka must have come by, drunk, they conclude, and picked a fight.

Reeling from tens of thousands of refugees returning from Sudan’s long civil war, ethnic tensions, and the difficulties of setting up a new government, South Sudan is the only developing country I have heard of for which a proliferation of international aid organizations has not created two fully separate and distinct economies—one for natives, and one for developed-country visitors. Instead, food, especially produce, is expensive for everyone, and many staples of American life—including lettuce and other salad staples—are frequently unavailable. And, most improbably, just about nothing people eat is grown or raised there. If you eat anything in Juba, chances are high that it came from Kampala, Uganda, 800 kilometers and a lifetime away; exceptions are luxury goods, which tend to come from Nairobi, Kenya, Sudan’s much wealthier northern neighbor.

Despite rapid growth and rebuilding, unemployment is also high in Sudan, particularly for the native Sudanese. There are so many reasons for this, so many factors at play—prejudice, for one, and the foreign money in the region that lures immigrants from other countries to work in Juba—but one of the biggest handicaps is a mental block caused by decades of civil war. They don’t teach you this in class, of course, but it seems to me that if, for 50 years, life is so chaotic that your actions don’t necessarily relate to any effects—aid drops from the sky, or doesn’t, without your input, your house stays up or falls regardless of whether you reinforce it or not, and you may or may not get paid for a day’s work—you lose sight of cause and effect when things begin to settle down. As you might imagine, this situation leads to a weaker workforce, and employers facing this mindset frequently do better if they discriminate against those most likely to have it.

My favorite story about this situation is one about a hotel in Juba. While I can’t vouch for the accuracy, I did hear it separately from two people who had lived in South Sudan for their entire lives. They told me that there was a relatively nice hotel in Juba, staffed mostly by locals. Two women on the cleaning staff did not show up to work regularly or on time, and frequently did not do their duties while at work. When they were fired, they went back to their village and brought back the entire village for support. The villagers tried to burn the hotel down in protest, a type of community justice common in this area. When the police were called, rather than dealing with the angry villagers, they arrested the hotel owners.

Similarly, my students frequently had trouble with cause and effect when it came to advocacy. The first part of my class focused on defining problems that the organization’s advocacy work could address. This was not a problem for the class, and they easily came up with several ideas. The second part, solutions, was a lot harder. Much to my frustration, I frequently found myself having the following conversation:

Tanya: “Okay, you said that the problem you want to solve is that people do not understand the relationship between sex and HIV, how do you think we can address that?”

Student: “They don’t understand.”

Tanya: “Do you think you could teach them? We could work on teaching and communication strategies.”

Student: “But they don’t understand.”

Tanya: “What would help them to understand? What helped you to understand?”

Student: “No, but… they don’t understand.”

Admittedly, being young and inexperienced, I could be misinterpreting this conversation, but what I got out of this experience, and confirmed with those who had been in the field longer, was that the miscommunication wasn’t in the words I was using—it was in the very idea that the class’s actions could affect change in the future. A challenge, indeed, for an advocacy-strategy class, and one I sincerely hope that I, at least, lay the foundation for overcoming. I was left with one thought, though: “What better way could there be to help a society to adjust to a peaceful situation in which personal efforts are needed to sustain growth than to encourage self-reliance through homesteading, to help people to rely on themselves and their neighbors to grow their own food, prepare for the dry season, prepare for the next growing season, and to watch the fruits of their labor develop in the course of months, rather than years.”

In stark contrast to this problem with sustained effort and cause and effect, I found myself awed by the level of faith held by so many in the area, and by people’s commitment to growth. I attended a conference for Christian Juba University graduates on their role as Christians in dealing with social and development issues. I missed the section on HIV/AIDS, instead, arriving on the day in which the group was discussing integrity in business, and how problems among the Sudanese with a lack of integrity was damaging the economy and leading to problems domestically and internationally. I was, frankly, terrified that my conspicuous white face would lead to difficulty, that my face would be seen as one of judgment, but I was welcomed at every turn. At services on Easter Sunday, each church was filled with men and women singing. They welcomed everyone who came, friend and stranger alike, and made time to study together in small groups several times a week. I was particularly struck by the pastor, who spoke of the role of the church and faith in creating a better and stronger future, of building a community that can overcome the hardships that they have faced in South Sudan; even on one of the holiest days of the year, the Sudanese were focusing on working hard, growing, and becoming stronger.

I found some irony in the fact that my class, which included at least one former child soldier, was held in Totto Chan, an old child trauma center. The trauma program ended two years ago, and now the building has that has lapsed into a sort of social services bureau. It’s a luxurious building, there is usually enough power to run lights, an air conditioner, a laptop, and a projector. My students tried to charge their cell phones there, rather than paying at the market or risking overloading their generators, but inevitably someone would try to add one charger too many, and everything crashed.

* * *

On the last day of class, at the graduation ceremony, a colleague asked the class to thank me for coming, adding that it was very difficult for most western visitors to make the trip and stay there. At the time, the only real difficulty that I could think of (other than the inevitable upset stomach) was that even the relatively luxurious class building didn’t have a working toilet—the bucket system was the best they could provide. Upon reflection, though, the hardest part of being there had nothing to do with the living conditions in South Sudan: the hardest thing was to see how far the region has come and know how far it has still to go.