It was a simpler time, before railroads were built or the coal industry and tourism began to change the landscape. Back then, existence was all about independence, energy, and self-sufficiency. It was in these days that the manufacture of illicit whiskey grew to be a huge money maker for the Appalachian mountain people, and that’s the reason it thrived for so many years.

Men were willing to risk their welfare and their very lives to construct a still and go through the tedious process of making the whiskey. The money it brought in helped feed their families and made it possible for them to buy the necessities of life. There were several kinds of moonshine whiskey made back in the hills: corn, rye, wheat, seed cane, and sugar liquor; the most popular being corn. Several kinds of fruit brandy were also made; apple, banana, and blackberry to name a few. Those who made no more than a few gallons of whiskey a year became moonshiners and sold the stuff to trusted friends and relatives.

But then several things began to happen. Modern medicine began to take hold and the corn whiskey that was an essential ingredient in many home remedies was suddenly not so essential. Also afoot was societies increasing affluence; young people flocked to the cities and towns to find easier ways of making a living than moonshining. Then greed set in; big city mentality showed moonshiners how to double their production and their profits by skimping on ingredients and hurrying up the process. The days of “the finest home brew that no one makes like that anymore“, passed into oblivion. As the original moonshiners died off, and there was no one to take their place, moonshining went the way of the dinosaurs.

In The Beginning… The History of Moonshining

Moonshine, also known as corn squeezins, white lightnin’, ruckus juice, and thump whiskey, hails back to the 1700’s when Scotsmen immigrated to the Appalachian Mountains of Western Pennsylvania. They brought with them their knowledge of still making; and many Appalachian moonshiners were descended from these very folks.

So named because it was done by the light of the moon to hide the smoke it produced, moonshining has been a clandestine craft since the days of the Revolutionary War when our government began trying to get what they considered their fair share of home-brewed hooch.

Moonshine and the Long Arm of the Law

Moonshiners resisted all attempts at outside restraint; this behavior won them the reputation of being hardy survivors who lived on their own terms. In Civil War days, grain needed for the making of corn squeezins, was prohibited for use as anything but food, and home distillation was outlawed; this ban was hard to enforce. After the Civil War, a federal tax was put on home-distilleries. But in order to tax a still, the government had to know who actually had one, so they again met up with a brick wall and the tax was virtually ignored.

Attempts at enforcing the tax led to informers, vengeance raids, moonshining clans and shoot outs with revenuers. Some moonshiners became ruthless and informed on each other to gain a rivals market. Other people worked as revenuers in one state and ran moonshine in a neighboring state. The battle raged on for years, neither side ever being able to completely eradicate the other. Making whiskey was how folks got cash for things they couldn’t make or grow themselves, like salt, sugar and shoes. They weren’t about to let the “revenuers” and their volunteers, called “revenue dogs”, take that away from them or tax it out of existence. Moonshiners became known as vigorous individuals willing to stand up to authority, true to their Scottish ancestry.

Then along came the 1920’s and Prohibition, again the government thought they could reign in moon shining; again they were very wrong. Their newest scheme only caused people’s thirst to increase and stills worked overtime to fill the demand. The whiskey made in the backwoods was often shipped to bootleggers in the big cities, increasing the moonshiners profits even more. During the days of Prohibition, the buying of home-brewed whiskey continued to be a relaxed, over-the-back-fence kind of thing; business was conducted efficiently yet without any sense of formality.

After Prohibition, moonshining arrests were left up to local sheriffs, putting the sheriffs in the awkward position of having to arrest people they’d known all their lives. Moon-shining was a widely known and accepted practice in the hills; there were times when a local sheriff had to “arrest” a moonshiner. Afterwards, the whiskey was simply poured out, the sugar used to make it donated to a school or hospital and the copper in the still sold. The farmer went right back into production, starting from scratch. Friendly relationships between the law and blockaders was often the norm; when a sheriff said to a moonshiner, “I hear you’re farmin’ in the woods”, it was code to let the farmer know to watch his step.

Changing Times in the History of Moonshine

As time went on, being a moonshiner became more and more risky and difficult. The cost of sugar tripled in the 1950’s, and being a key ingredient in certain types of spirits, production was necessarily shut down in more than a few stills. The Blue Ridge Parkway was built in the 1930’s as a tourist route. Even though it was used to haul whiskey to Washington DC, a lot of land was taken up in the building of it and it was pretty heavily patrolled. This cut down on the whiskey trade substantially. As businesses sprang up along the parkway, bringing more and more people and jobs to the area, men began to find easier ways to make a living. Most of them would rather work a steady job and get a regular paycheck than do the hard, dirty work of moonshining and risk the four year prison term it brought. The days when a boy could start out in the trade as young as seven years old and be working full time by the age of 16 were fading fast. But even today, Wilkes County, NC, where a lot of the original moon shining took place, is still considered the “moonshining capitol of the world.”

“Pure Corn”: The Moonshine Recipe

There are as many recipes for moonshine as there are names for the stuff, but what follows is pretty close to the original. To start out with, you’ll need nine to nine and one-half bushels of white corn, don’t use hybrid or yellow corn. Put one and a half bushels of the corn aside to sprout; once this corn is sprouted, it’s called malt. The day before the malt is ready, ground the other eight bushels of corn , grind it fine, this is called mash. You can use sugar or not, but remember that sugar slows the process down and pure corn whiskey does not have sugar in it.

When the mash and the malt are ready, put them in your barrels, mix with water according to your recipe, and allow it all to work until it becomes beer. In this case beer is the fermented liquid made from the corn meal bases. When this mixture is cooked in the still, it makes moonshine.

Heat the beer to a hard boiling point, when the boiling slows, that’s when the whiskey actually starts to be made. The process is a lot more complicated than this, and quite time consuming and tedious, but you get the basic idea. The old-timers went to considerable trouble to follow the recipe to the letter, attending to every detail and not rushing the process.

If You Want Good Whiskey…

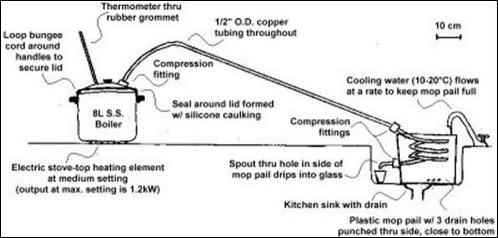

Always build your still out of copper, it distributes heat better, the beer won’t stick to it as much and there’s less chance of metal poisoning. Stills made out of iron and tin will burn the beer, giving the final product an off taste.

Avoid adding potash and ground up potatoes to the malt for a higher yield. Potash is poisonous, yet the unscrupulous moonshiners of latter days actually used it; there’s that greed thing rearing it’s ugly head.

Don’t make your run too early before the beer has a chance to sour properly. A run is when the contents of the still are run through the entire operation once. Always go for quality over quantity. Use the best water you can find and be sure to keep everything in your operation as clean as you can.

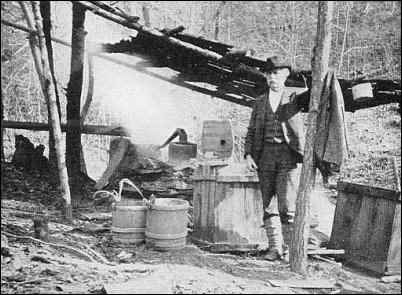

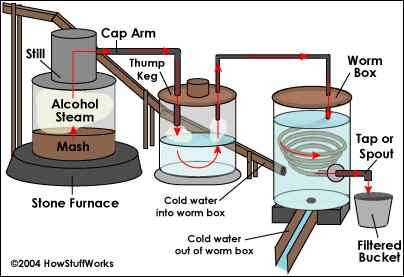

The Basic Moonshine Still

Again, moonshine still designs were numerous and up to the individual and what he had on hand.

The main parts are the cap, usually a fifty-gallon barrel. The cap is the top third of the still and sits on top of it; it’s removable so the still can be filled after a run. The still itself is a big barrel; its capacity can be as much as five hundred gallons.

The firebox is the source of heat and where the wood is fed into. Hard woods like ash or hickory were customary as they produced less smoke and gave a good, steady heat. The heat is drawn in and around the lower part of the still and out the flue.

The furnace is a stone structure in which the still sits for heating. The furnace is best made out of natural stone with red clay chinking that will harden with successive burnings. Any number of extra barrels can also be used in the stilling process.

These are your basic still parts, with any number of pipes, barrels and boxes added as each man saw fit.

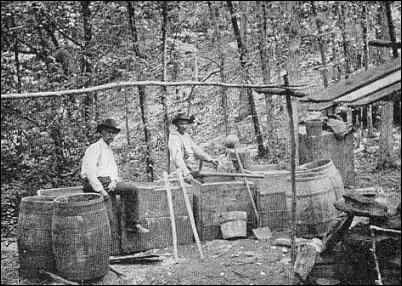

Hiding the Still

The method and the moonshine of the hill people were both widely respected back in the day, and blockaders went to great lengths to hide their stills. A favorite technique was to find a tree that had fallen over a gully and build the still underneath it, adding extra branches for cover. If a moonshiner was fortunate enough to find an old cave, he could cover the entrance and set up his stillin’ operation inside.

Another common trick was to locate a large laurel thicket, cut a room out of the middle and build the still inside. Since cold running water was needed to make the best moonshine, stillers tried to set up shop as near the source of a stream as possible, sometimes they positioned their operation in a dry cove where there was no stream and piped in water from a wet cove higher up, being careful to run the piping underground all the way.

Abandoned buildings or spots where a still had just been taken down by a revenuer were thought to be ideal; the belief was that these spots would be ignored for some time. Another technique was to dig out an underground room big enough to stand in, camouflage it and put a trap door with a vent pipe in the roof. This proved to be the perfect place to run production.

To hide the smoke from the still, some would run pipes so the smoke would come out underwater and some would burn the smoke by piping it out the side of the furnace on the still and recirculating it back into the firebox.

Hiding the still was one thing, but moonshiners also had to be careful to cover their tracks and any evidence of their operation. Great care was taken to muffle sounds that would carry for miles in the woods, like the sound of a hammer against metal. Any leftover supplies like empty sugar bags, jar lids and pieces of copper were tip-offs as well and couldn’t be carelessly left behind. Hogs loved the corn mash that whiskey was made from and care had to be take to prevent them from finding the set up and falling into the mash boxes. If a farmer had free-ranging hogs, fences had to be put up around these boxes. An informer was the most common way that a still would be found. A neighbor who had a grudge or an ax to grind could easily befriend a moonshiner, buy his product and turn him in to the next revenuer that came nosing around.

In Conclusion

Moonshining has to be one of the most fascinating endeavors people have ever attempted. It’s both glamorous and grungy; its mystique no doubt drew people to it, and may still be drawing them. There are harsh penalties for the practice of stillin‘, and it remains hard, hot and dirty work for the most part. Many recipes involved at least 75 pounds of white corn meal, 300 pounds of sugar, a pound of yeast and 300 gallons of water, ingredients hard to come by back in the hills. Maybe these factors add to its charm, maybe not. But moonshining, if it’s done at all today, is a far cry from the fine art as it was practiced back in its prime.

Sources:

The Foxfire Book, Anchor Books Edition: 1972 by Brooks Eliot Wiggington

Department of Anthropology, Appalachian State University: “It’s All Legal Until You Get Caught: Moonshining in the Southern Appalachians” by Jason Sumich, 2007

Our Appalachia: An Oral History Edited by Laurel Shackelford and Bill Weinberg, copyright 1977 by Appalachian Oral History Project, Hill and Wang New York

“Easy Homestead Moonshine”, by Anthony Okrongly, Homestead.org,