Modern American homesteading, to misquote The Bard, makes strange bedfellows.

Who can deny that communists, communalists, socialists, utopians, fundamentalists, survivalists, innovators, traditionalists, hermits, poets, junkyard doggers and a myriad other ists and ites have based their lives around what one author referred to as “earth hunger?” People who would not want to be seen at the same protest rally or possibly even the same grocery store as their fellow homesteaders, separately yet equally embrace the ideals of land ownership, self-sufficiency, simple satisfactions, homegrown food, handcrafted toys, and hand-sewn quilts. The Amish, those most peaceable and pacifistic folks, thus link arms with those who are storing up arms for the coming Armageddon. It would be humorous if it weren’t so profoundly important. Important because it continues to inform us about who we are.

After World War II, nationally sanctioned homesteading was no more in America, except for some large-scale ranching initiatives and an attempt to make the Alaskan wilderness look attractive to more than the local bears. Yet the concept did not disappear. It cannot, perhaps, because it taps into a basic set of desires that we Americans commonly experience: the desire to eschew or otherwise overcome the rat race of money labor; the desire to eat and drink fresh, wholesome foods; the desire to unlock from “the grid”; the desire to feel the weight and texture of something one’s own hands have created; the desire to inhale the smoke of one’s own home fires and warm one’s boots at said fires if and when one wishes, for as long as one damn well pleases.

Early in the twentieth century, a Londoner (William J. Dawson, The Quest of the Simple Life) coined the term “earth hunger.” He did the math, acknowledged that much of the salary he earned as a clerk was spent to survive economically in the city, never getting ahead, never really having more than a meager chance for enjoyment. He moved his wife and two sons to a cottage in the wilds of the Lake District and there led an idyllic life: cozy, cheap and inwardly rewarding every single minute, as he depicts it. Well, he was also a writer, so we must excuse him if he gilded the goldenrod just slightly, and thank him for painting a portrait of what most homesteaders believe they will enjoy when they find their “five acres and independence” (to quote another homesteading writer, Maurice G. Kains, an American who wrote a classic by that title from a horticultural perspective in 1935). Bolton Hall (Three Acres and Liberty) an American agrarian and thrifty living proponent, writing around the same time as Dawson, was already decrying the inflated price of land (as much as $100 per acre!).

Reading makes a good pastime on the homestead, and many homesteaders are unusually literate. Wasn’t it the writers who got us on the move in the 1950s and 60s, got us On the Road so that ideas like the back-to-the-land movement could cross-pollinate with other big theories on the go, about the medium being the message and communes, geodesic construction and banning The Bomb, organic foods and sanpaku, and war/military industrialism being dangerous for children and other living things?

No retrospective on American post-war homesteading would be complete without a tribute to Helen and Scott Nearing. Wanda Urbanska (see Signposts to Simplicity on Homestead.org) cites a chance to hear the Nearings speak as an early influence on her complex thinking about “simple living,” spawning ideas that later grew into the PBS series by that name.

Long-lived (Helen died at 91 and Scott at 100), the Nearings’ philosophy developed with the century, always rooted in socialist idealism and a strain of American puritanism (though they might have rejected that notion, being in general, unreligious, anti-mainstream and anti-American-government). Their rigid plan for how to use one’s waking hours might strike present-day homesteaders as needlessly restrictive. They practiced as well as preached a daily lifestyle that involved four hours of civic activity, four hours of “bread labor” to maintain basic food, clothing and shelter, and four hours of professional pursuits, some of which was spent in writing their well-read classic, Living the Good Life, first published in 1954. Few tomes have had as great an influence on the homesteading explosion of the ensuing decades. By the 1970s it was virtually the family bible for hip and post-hip homesteaders. The Nearings were in large part responsible for bringing the word “organic” out of its musty closet and making it part of the parlance of modern life.

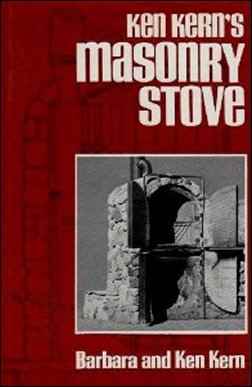

And there were other books we perused, and should continue to consult, books that set us on the pathway to the big disconnect from urban to “rurban” or agrarian. Ken Kern, a self-published construction theorist who ironically died with his house in a freak windstorm, wrote The Owner Built Home and The Owner Built Homestead, advancing ideas for passive solar and innovative construction techniques that are as sound (and as radical) today as they were in the early 1970s. In 1978, he penned The Healthy Homestead, promoting the almost unheard of notion that modern houses could be toxic. In the Seventies, it was not uncommon to see homesteaders building their dream cabins with a copy of one of Ken Kern’s books stuck in the back pocket of their Levis.

The Foxfire Book (later a series) was a subcultural initiative that revived hardscrabble life skills from Appalachia. Popular monthly mag, Mother Earth News, started on a shoestring and has survived to the present era. Bradford Angier, known as “Mr .Outdoors” was an early survivalist writer (How to Build Your Home in the Woods, etc). For foragers there was Stalking the Wild Asparagus by Euell Gibbons, who though an eccentric, managed to get a seat on the Johnny Carson Show, encouraging Americans to collect and consume odd and neglected foodstuffs.

John Jeavons wrote How to Grow More Vegetables Than You Ever Thought Possible on Less Land Than You Can Imagine, another widely read homesteading classic, in the mid 1970s. A Texan who went to Yale, worked overseas for USAID but was ultimately stopped in his tracks and captivated by the work of gardener guru Alan Chadwick, Jeavons was a proponent of double digging, raised beds, canopy spacing to reduce weeds, and other seminal techniques that changed the way some of us felt about gardening forever. Double digging, Jeavons saw with his own two peepers, yields two-fold, with more and healthier plants. Jeavons’ method harked back to Rudolf Steiner’s system of biodynamics as well as leaping forward to the latest ecological best practice. Jeavons has become a well-recognized expert, a much-awarded leader of the biointensive agriculture movement, and a grand old man of the alternative living cohort who has yet to rest on his well-deserved laurels.

Towering above the hip-pocket paperbacks available for the homesteader wannabe was a giant cornucopia of desirable tools and other wonders that came complete with a portrait of the earth suspended in the blackness of space, at the time a truly far-out artistic and philosophical conception. The late Steve Jobs remembered: “When I was young, there was an amazing publication called The Whole Earth Catalog, which was one of the bibles of my generation…. It was sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along. It was idealistic and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.”

Stewart Brand, the entrepreneurial mind behind the WEC, started the catalog with a “truck store” of tools and books. He decided to do Sears Roebuck one better with a planet-friendly collection of home-handy goodies readily accessible to the rugged individualist, the introvert, the nerd in his lab, the grizzled dude in his man space, and the women behind them all with clothes hanging on the passive solar line and organic apple pies oozing over in the oven.

The book was not only large in dimension (11” x 14” x 1”) but in the depth and breadth of what it offered for sale and for intellectual fodder. There was something about its grainy newsprint that made you feel sure the products were produced with integrity – and in almost every case, they were. I can remember ordering a sealed container of seeds designed to survive a nuclear holocaust and provide vegetables enough for a family of four for a year after the imminent apocalypse we all expected, the time when California was going to break off along the San Andreas Fault line and sink into the Pacific, while on the other side of the US, the lost civilization of Atlantis was going to rise again from the Bermuda Triangle in all its fabled glory.

The WEC, which was published regularly from 1968 to 1972 and sometimes after that, contained gritty and visionary articles by such cultural luminaries as Ralph Nader, Wendell Berry, Ivan Illich, and Wavy Gravy. And though it was clearly leaning so far to the left as to be teetering on its sandals, I’m sure it has found its way into the homes of survivalists, gun hoarders, and break-away Mormon polygamists, all preparing for their own version of the End Times. I had a friend who emerged from a smoke-filled yurt in 1971 to see a copy of The Last Whole Earth Catalog on a communal dining table. She told me, “Then, man, I knew It was Over.” It was not, however, nor was that really the last WEC, since the publication was so overwhelmingly popular among its fiercely loyal fans that its creators were forced to reprise it several times more. My friend, like Jobs, was enamoured of the “last” WEC cover’s Zen-like advice: “Stay hungry; stay foolish.”

So, armed with a mystical mantra and many glorious guidebooks for growing good greens, sometime between 1950 and 1999, a lot of people hopped off the grid-like scalded fleas and headed for the Ozarks, or the North Carolina mountains, or desert landscapes of New Mexico and Arizona, or remote wildernesses in Utah and Montana.

I have friends who in the mid-1970s became disgusted with the tangled maze of zoning regulations about minimum square footage, percolation, and numbers of bathrooms – in short, about everything that crimped personal housing freedom – in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. They Okied out to Arkansas where they became happy homesteaders on a way-back dirt road. They bought land and slept under a tarp until their handmade house was dried in. The land they paid a pittance for has increased in value, bringing with the increase an increase in neighbors, tourists, and, you guessed it, zoning. And rules. And regs. And asphalt for the road. And invasions of privacy via the school and healthcare systems. But it’s okay, because by the definition previously established in this series of articles, my friends stopped homesteading at some ineffable moment, and now are simply – at home.

Post-war American homesteaders started artist colonies, home businesses, farmer’s markets, organic growers societies, communes, publishing companies, blogs and in some cases really large families. Some drifted on, as was their probable original intent, while a few soured on the whole deal and begged for a seat at the table of illusive prosperity back in the city. Many so offended the locals with their Sixties ethos of free love, nudity and drug use that they were driven out. But many persisted, mostly those who toiled alone or in small groups, with serious intent. Homesteading is not for the faint of heart; to make piece of land, even good land, produce enough for real self-sufficiency requires an integrated mind and a very strong back.

These days, as is well known, prices of land and especially improved land have shot through the ceiling, making it increasingly difficult for young people to skedaddle off the grid. Homesteading has become a thought-out step for the wealthy who want to back away from the grid with a show of grace, not for the broke (the hungry and foolish) who would do so upon a sudden whim that takes no thought for the morrow. Many who may wish to go back to the land will be turned back by real estate sticker shock. Their “earth hunger” may have to wait for a windfall. These dreamers are still able, however, to piggyback on earlier endeavors, to join communal groups already in train, the best known of which is probably The Farm in Tennessee. Renting is affordable in some of these intentional communities, but buying can be as expensive as anywhere. It is almost impossible anymore to protest high prices by buying cheap.

But it is simple to live more simply.

It is still feasible to take guerilla actions that yield some of the same satisfaction as once could be experienced through the total retreats from the coldness of civilization. One can shop green and organic (no plastic bags ever, please!), practice urban gardening (make sure your town allows unsightly veggie beds in place of well-coifed lawn), and take eco-vacations, including stays with Amish/Mennonite families and internships on organic farms. If you can’t grow your own apples or cherries, you can at least pick your own. You can take the kids to the many demonstration farms that feature creatures in a gently supervised habitat available for petting.

My History of American Homesteading series began with the stern admonition of John Smith to our nation’s earliest colonists, that “He who does not work shall not eat.” It ends on a lighter note, perhaps redolent of our times: the sense that homesteading can bring happiness, that it has a higher purpose than mere feeding, though the joy of feeding oneself by one’s hand labor is part of the attraction. If undertaken with intention, those who go back to the land can make a house a home, and a piece of land not just a financial investment, but an investment in nature and in future.

Though most folks today don’t worry about (or wish for) an apocalypse to send the nation plummeting back in time…well, let’s just say, if it were to happen, some of us would be ready for a new start.

And if you’re lucky, we might lend you an axe.

I just discovered this series “History of American Homesteading” and am enjoying it thoroughly. Thanks for publishing it!